Review | In My Old Home, academic Orville Schell turns to fiction to make sense of China’s Cultural Revolution

- Orville Schell structures the book as a bildungsroman that follows protagonist Little Li’s journey from innocence to experience

- Historical interjections and a commitment to translation give the sense of an expert unwilling to entirely yield his mantle to his story and characters

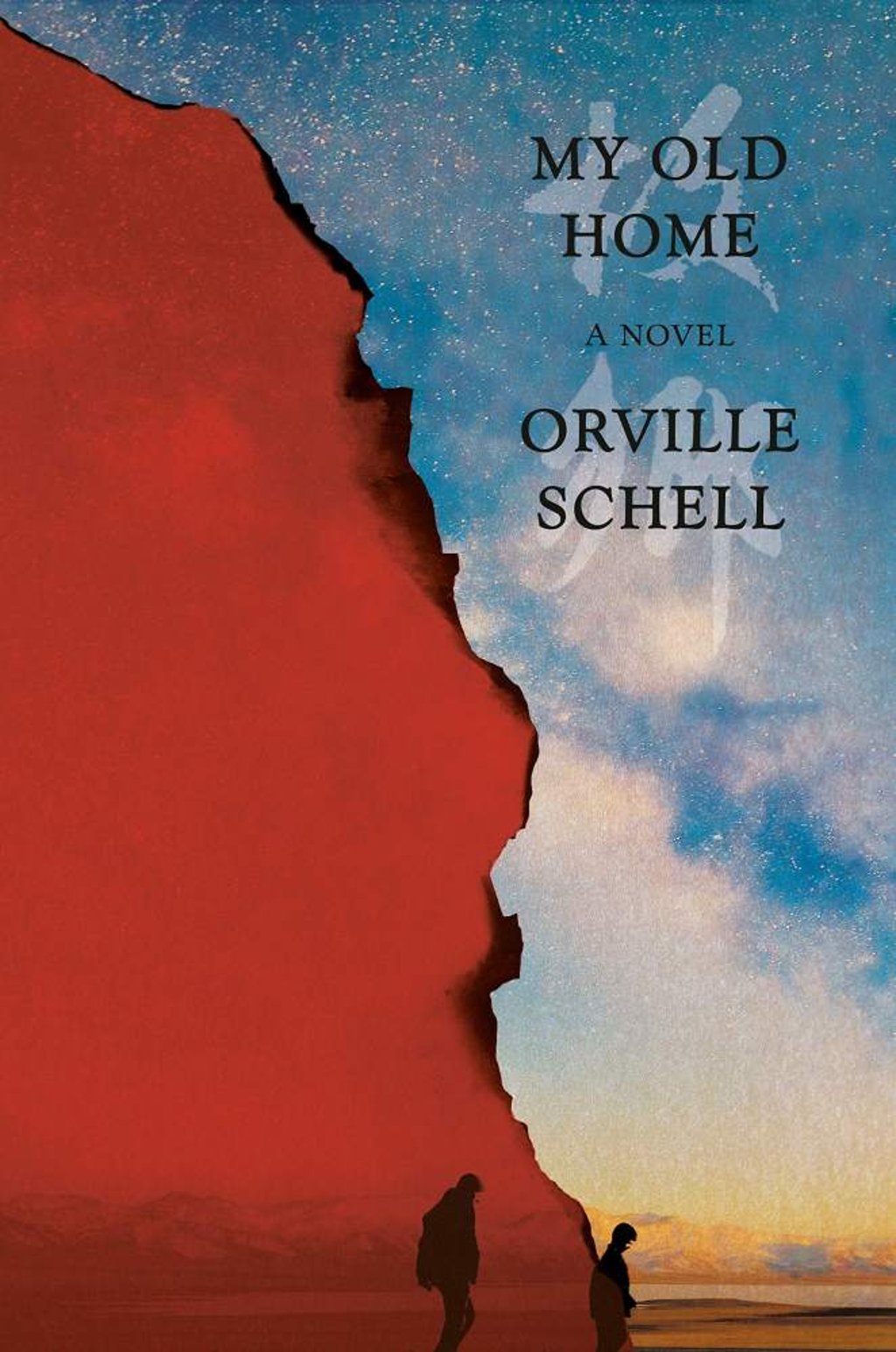

My Old Home

by Orville Schell

Pantheon

In the hours before dawn on August 18, 1966, the vast expanse of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square began to fill with people. By the time Mao Zedong walked onto the rostrum of the Gate of Heavenly Peace, clad in an ill-fitting People’s Liberation Army uniform, there were more than a million crammed into the square and the streets around it.

Lin Biao gave a speech to the assembled crowd in which he cited Chairman Mao as the “greatest genius” of the age and encouraged the assembled Red Guards to destroy the four olds: the ideas, culture, customs and habits of the past. This first mass rally of the Cultural Revolution initiated the worst violence of what became known as Hong Bayue – Red August – during which many thousands of people were tortured and killed in Beijing by Red Guards.

“The screams of the beaten and dying made sleep impossible,” wrote American sinologist David Kidd of that terrible month. “By the end […] the dead were piled so high that they could not be burned fast enough.”

The story of China’s Cultural Revolution has been well told in non-fiction: autobiographical works such as Jung Chang’s Wild Swans (1991) and Ma Bo’s Blood Red Sunset (1995) have become bestsellers, while one could fill a decent-sized bookcase with English-language historical works on the era.

Historian Jonathan Spence observed that the Cultural Revolution is one of those rare historical events that seems to make less sense with the passage of time, and despite all the factual writing that has been produced on the decade from 1966 to Mao’s death, in 1976, it remains a confounding period to understand both in terms of personal motivations and the political and cultural forces at play.