Review | A Chinese Papillon: the true story of a man who escaped Mao’s labour camps

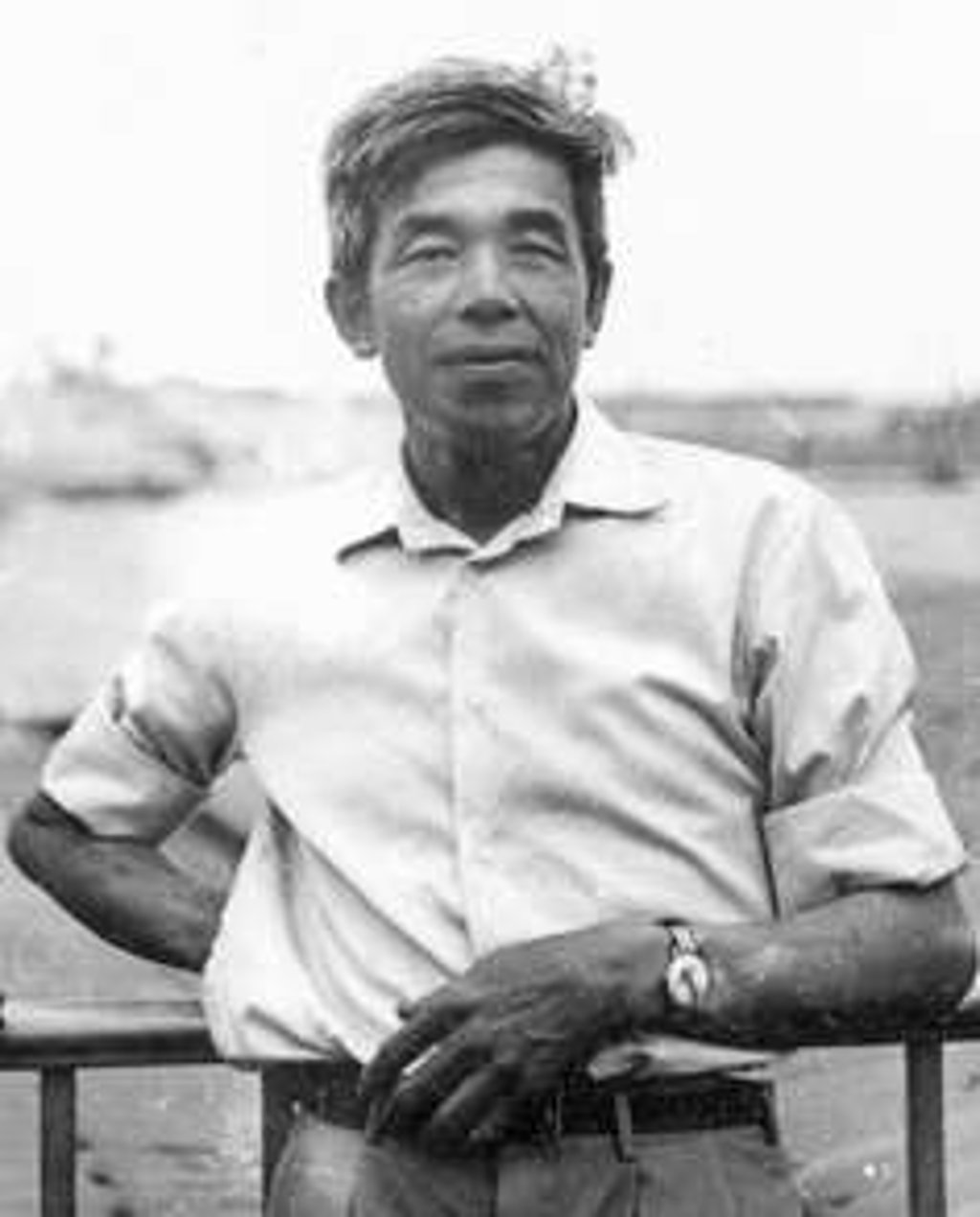

Xu Hongci is one of a tiny number of escapees from the prison camps of Maoist China; his autobiography has been translated into English from the Chinese original, published by Hong Kong bookseller Lee Bo in 2008

by Xu Hongci (translated and edited by Erling Hoh)

Sarah Crichton Books

There are no stories more satisfying than those in which the common man suffers injustice and cruelty at the hands of the powerful but perseveres against all odds, clinging to his values until he can claim victory. They’re all the more compelling when true, and never more so than when the story goes public against the wishes of the antagonist.

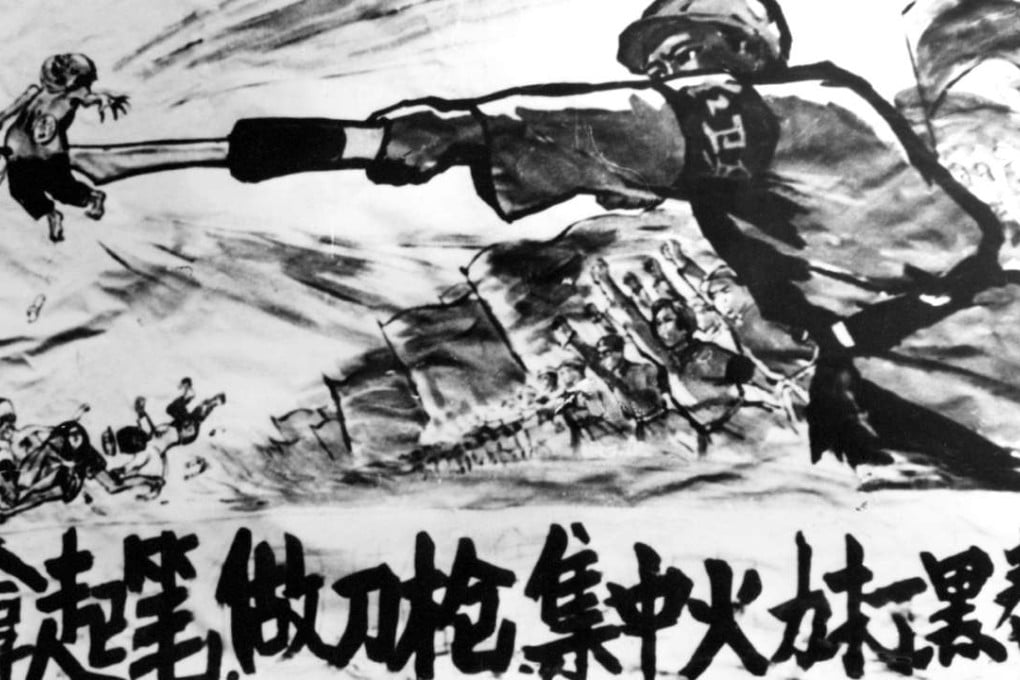

No Wall Too High measures up on all counts as Xu Hongci, a Chinese medical student and intellectual, tells his story of enduring 14 years’ hard labour, suffering torture and starvation, before escaping to Mongolia.

Swedish journalist and translator Erling Hoh was researching a novel about an escape from a Chinese labour camp when he found an obscure Chinese version of Xu’s story in Hong Kong’s Central Library. Instead of writing a novel, he translated Xu’s heart-wrenching tale.

Escape from the Laogaicame out shortly before Xu’s death, in 2008. It was a transcript of an interview Xu gave to a journalist, Hu Zhanfen.Its publisher, Lee Po, formerly known as Lee Bo, was one of the five booksellers who disappeared in the winter of 2015-16, and were widely believed to have been detained in China. That book might not have found a local publisher in the more fearful atmosphere that has pervaded Hong Kong’s book industry since then.