Musician Olivier Cong’s latest album Tropical Church is an ode to Hong Kong via experimental sounds

Oliver Cong went from a brooding songwriter to an acolyte of the late Ryuichi Sakamoto – now his sprawling, interdisciplinary practice is hard to pin down

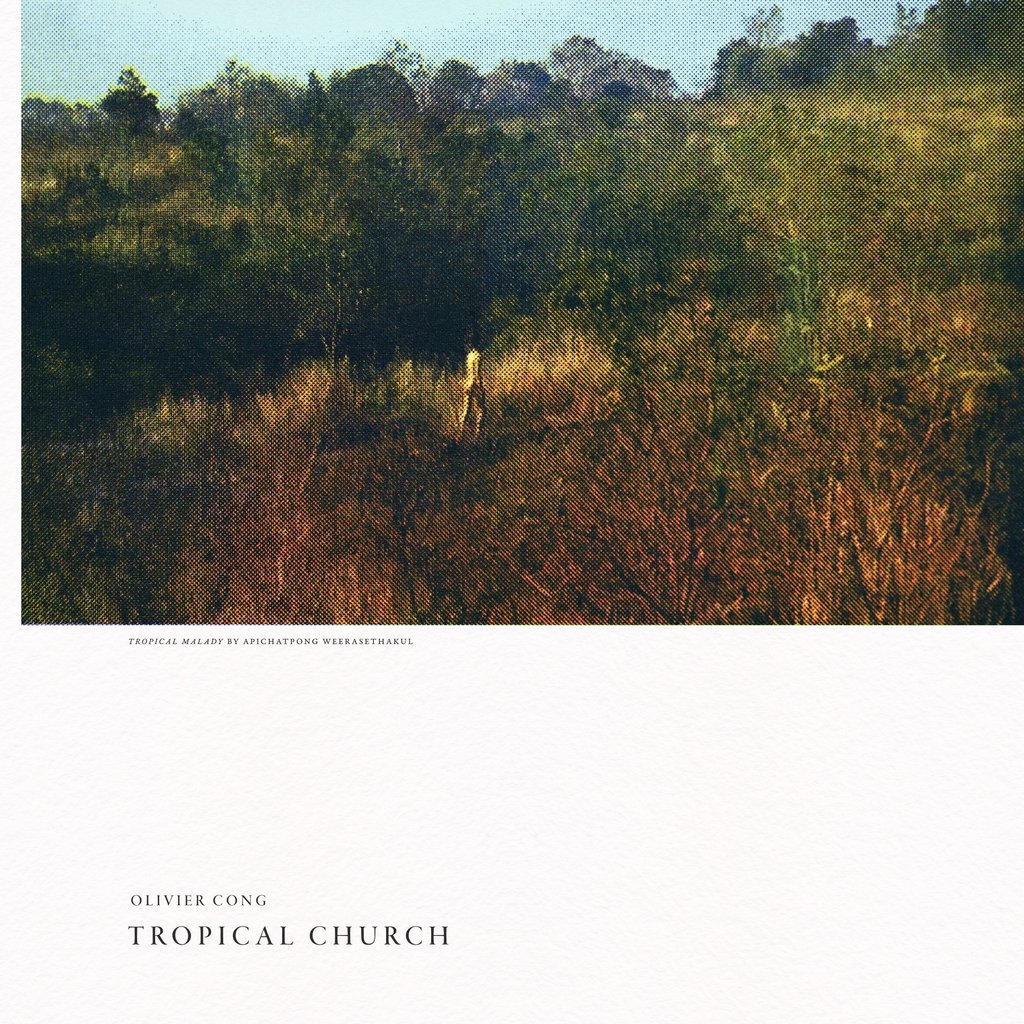

When Jean-René Olivier Yat Tin Cong Shoe answers the door to his studio, he is wearing a shirt with an Albert Camus quote from The Plague (1947), and his head is heavy from the remnants of a nightmare. The airy space in the heart of Ngau Tau Kok is an exercise in maximalism – everywhere, musical instruments, stacks of books and visual references such as a picture of Maggie Cheung Man-yuk in Irma Vep (1996), and a small image of soft trees under the afternoon sun. The latter is a still from Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s 2004 film Tropical Malady, which is also the cover image of Cong’s new album, Tropical Church.

Cong has long admired Apichatpong’s surrealist films, among them Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) and Memoria (2021), citing the Thai filmmaker’s ability to capture temperature and humidity – something Cong wishes to do with his music. When Apichatpong was in Hong Kong for his solo exhibition at the Kiang Malingue gallery in 2022, Cong went up to him, told him he was a fan of his work, and asked if he could please, please give him something to use. And so the director-artist gave Cong the image.

“In this way I’m quite like a child,” says Cong, who, aside from having managed to extract a piece of inspiration from his hero, now, at just the age of 29, has charted a career that includes interdisciplinary collaborations with the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, the Chung Ying Theatre Company and writer Hon Lai-chu.

But before all this, Cong, like many others in Hong Kong, had received a classical music education in piano and violin as a child. For university, he left Hong Kong to pursue a psychology degree in Southampton, lured there by the promise of the sea, but he found the English city dull, and himself isolated, homesick and with too much time on his hands. Seeking an outlet for his angst, he bought mics, keyboards and interfaces, and began composing.

Those demos eventually became the songs on his first record, A Ghost and His Paintings (2018), a moody, semi-gothic album that gave him a reputation of being a singer-songwriter to watch. The lyrics spoke of ravens, sandy shores and lost love, just the brand of melancholia that read earnest by virtue of his youth. Cong would play the songs live, with a guitar and several effects pedals over a series of small shows at indie venues, including at the now-closed art bookstore Mosses, and an intimate gig at a band practice space.

“I was younger, and I had a hopeful outlook on life,” says Cong. “It’s not the most outstanding album, but it’s an honest representation of myself at the time.”