Profile | Brazilian capoeira master ‘Eddy Murphy’ on teaching China the martial art, and how he got his nickname

- Born in the slums of São Paulo, in Brazil, Edilson Almeida had to fight the odds just to survive, until he was introduced to capoeira when he was nine years old

- At 54 and after two decades in Hong Kong, China and Macau, he is one of five masters in the premier organisation teaching the martial art, he tells Ed Peters

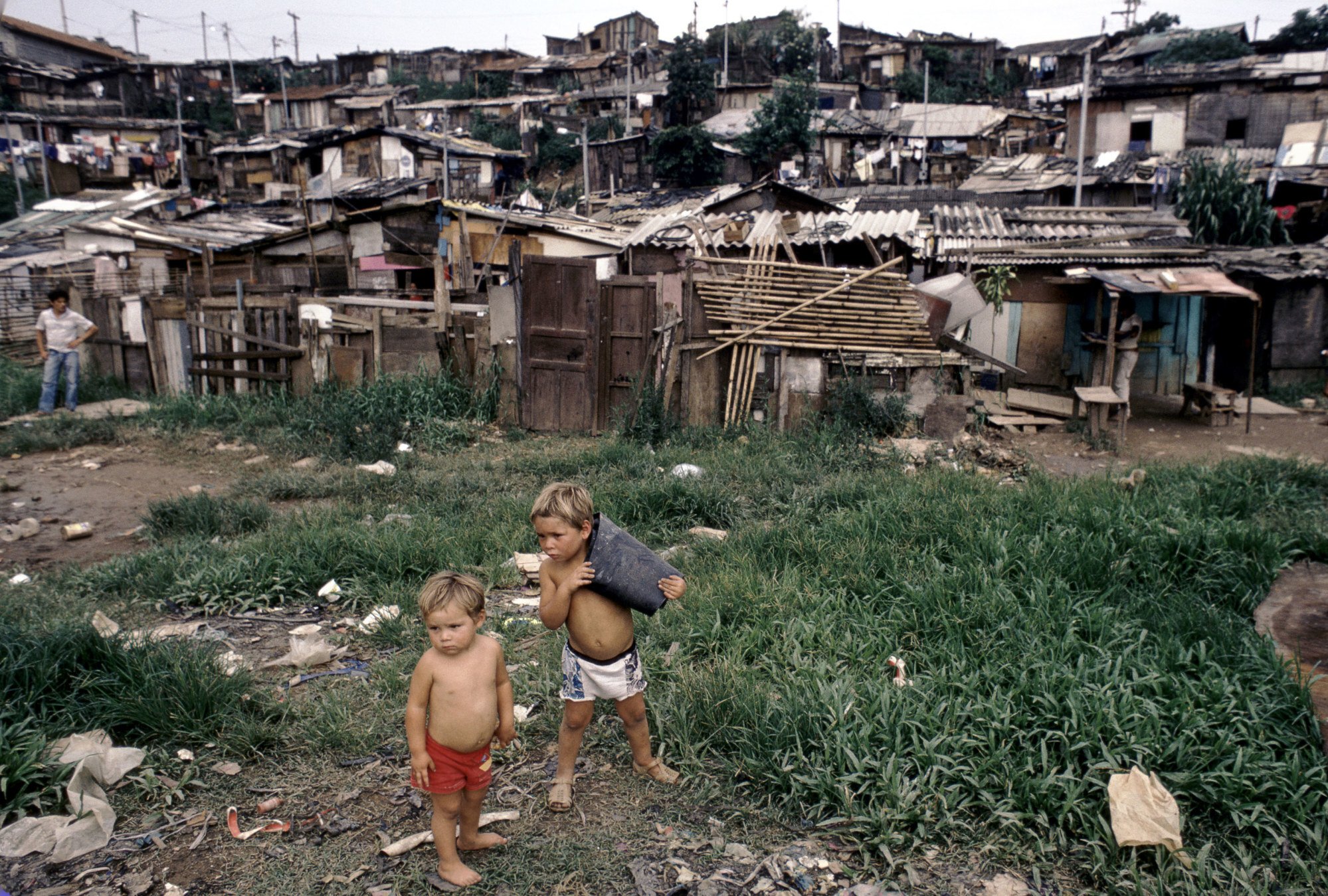

Starting small I was born prematurely, at six-and-a-half months, in the slums of São Paulo, in southeast Brazil, and was extremely lucky to survive. My father was a truck driver, and my mother looked after us six kids – I was the youngest – so with eight mouths to feed there wasn’t a lot of money left over at the end of the week.

I grew up small, skinny and extremely helpless in the sort of neighbourhood where I would have been at a disadvantage even if I’d been relatively healthy, but somehow I managed to fight the odds and survive. I did OK at school; I always used to have a big smile on my face and that helped me win a lot of friends.

New course Everything changed – and by that I mean the whole direction of my life and its meaning – when I was nine years old. It wasn’t so much a case of my getting into capoeira, Brazil’s signature martial art, as capoeira getting into me. I was taken up by one of the city’s top capoeira practitioners, Mestre Big Dinho, and he taught me my first ginga, which is the fundamental footwork that looks more like a rhythmic dance step than an orthodox fighting stance.

Capoeira’s been at the centre of my existence ever since. I’m 54 years old now and a mestre (master) myself, one of just five in the Grupo Axé Capoeira, which is the premier organisation teaching the martial art.

Cultural legacy Capoeira is a fully fledged martial art, but it started out as a way for slaves in Brazil to defend themselves, to react quickly and avoid being hit, as well as training them to trip and kick. It was disguised as a dance, which is how it came to be accompanied by music. Brazil abolished slavery back in the 1880s, but capoeira has endured, and Unesco recognised it as part of the country’s unique cultural heritage.

After qualifying as a capoeira instructor I moved to Barcelona, Spain, where I taught in a gym and also worked at a theatre that staged Brazilian cultural performances at weekends. Then, in 2000, I was offered a six-month contract in Hong Kong by a company that staged cultural events. As soon as I was sure I could bring my wife, Fernanda Matias, with me, I accepted like a shot.

China pioneer I did not expect to end up in Asia, but life has a mysterious way of showing us that if we are ready we should not only take an opportunity but also make the best of it. Luckily I was ready – and it was one of the best decisions of my life.

Two decades ago, people in Hong Kong had no idea about capoeira, so being the pioneer who first introduced it to China was a bit of a milestone for me. Despite the obvious cultural differences, we found some similarities because Asians have a big respect and appreciation for martial arts.

I used to train by myself in Victoria Park and people would stop and stare and ask if it was a dance, or martial arts, or acrobatics, and were fascinated when I said that it is all those things rolled into one. I’d invite them to try and then start to teach them then and there for free. More people would come along each week, so that was by far the best publicity.

Television talent In 2003, we moved to Guangdong so I could teach capoeira there. I didn’t speak Mandarin so it was tough going at first. A TV station approached me as they were looking for foreigners with what they called “special talents” and I guess I fitted the bill. Then I got caught up in one of those unlikely-chain-of-events things. The staff at a gym in Macau saw me on TV and invited me down to do a demonstration, which they loved. As a result, I was later asked back to Macau as an instructor, but that job didn’t last, so I set up on my own – the Capoeira Sports and Cultural Association of Macau.

Within a few years we were running up to 18 classes a week for 15 adults and 120 kids and I’m proud to see two of my old students – Professor Titan and Graduado Chiclete – doing really well in Hong Kong, too.

Running in the family My wife and three kids all practise capoeira. Jackeline, Hugo and Khiari all experienced capoeira for the first time while they were inside their mother’s womb. I used to play the berimbau, a sort of musical bow that originated in Africa, and sing to them. They were capoeiristas before they were born. Hugo, who is 25 now, won third place in the World Capoeira Competition when he was only 21, competing with contestants from 70 other countries, and beating others who were much older and more experienced.

I am really proud to see him not just following in my footsteps but putting his own interpretation on capoeira. This is what family means to me; we are in the same fight, we work together towards the same goal and as a husband and a father, I couldn’t ask for more. I am complete.

Seeing the world In some ways, capoeira is like a second passport and being a mestre is a huge privilege as it opens so many doors. A couple of years back I travelled to 12 countries in as many months. I was especially impressed with Russia – the people in my classes there didn’t speak anything other than Russian, but they were really respectful. Respect opens up new ways to learn. Even the kids in my classes in Macau, and some of them are as young as three, are taught respect. And they are taught one other thing: when you come to class, you should leave all your problems outside the door and come in with a clear, open mind.

Never give up The Covid-19 pandemic has been a difficult time for all of us, but capoeira challenges people and their perceptions, so it’s a useful grounding; it helps you to resist and adapt. My students in Macau have given me the support to keep going via online classes – and we’ve now got more signed up than we had before the pandemic, maybe because people are looking for alternative ways to pass the time. And capoeira brings us together as a big family right around the world, with strong bonds and friendships that have helped resist the pandemic.

I think the most important thing that I’ve learned is to never give up. Becoming a mestre was not easy. So you should always keep an open mind and never stop trying. Sometimes you may want to go in one direction and you hit a brick wall. Don’t give up – there’s another door nearby. Step aside, open that door and keep going, because other opportunities are waiting for you.

Joking around By the way, I’m not really called Eddy Murphy. My real name is Edilson Almeida but sooner or later everyone gets a capoeira nickname. As a kid, I used to joke a lot and one day Big Dinho pulled me aside and said: “Right, from now on, you’re Eddy Murphy.” And as far as the capoeira fraternity is concerned, that’s who I am now.