Dinosaur hunting in Inner Mongolia: Gobi Desert a treasure trove for University of Hong Kong-led expedition

For dinosaur enthusiasts, the Erlian Basin, in Inner Mongolia, is still full of surprises, Cameron Dueck finds during a fossil-hunting expedition

It is 44 degrees Celsius on the floor of the Gobi Desert; the air shimmers and dances with the heat. My eyes swim with tedium after hours of staring at the gently undulating ground, trying to spot precious fossil fragments among the countless pebbles.

To my right, within shouting distance, a scientist stoops, picks at something on the ground, then squats down for a closer look. He digs with his hammer, the chink-chink-chink of metal on stone carried away by the hot, dry wind. A small fragment comes free and he gently rubs the dirt away with his hands before putting it in a small plastic bag.

This University of Hong Kong-led expedition is not the first to come looking for remnants of the dinosaurs that lived, 80 million years ago, in the Upper Cretaceous ecosystem of the Erlian Basin, in Inner Mongolia, on China's northern border. This ground has been searched for fossils repeatedly over the past century, but the earth keeps pushing them up, like presents. Each year, helped by rain, frost and scouring gusts of wind, the soil is eroded and more fossils are exposed.

"When you prospect an area thoroughly you pick up a large proportion of the fossils of interest, and it takes several years of erosion before more things start to come out," says Dr Corwin Sullivan, a researcher at Beijing's Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) and one of a dozen people in our team of fossil hunters. Sullivan, whose book was published recently, wears a wide sun hat and a large red backpack as he zig-zags across the desert. "We just need to wait for more erosion to take place here and give us another crop of fossils to harvest."

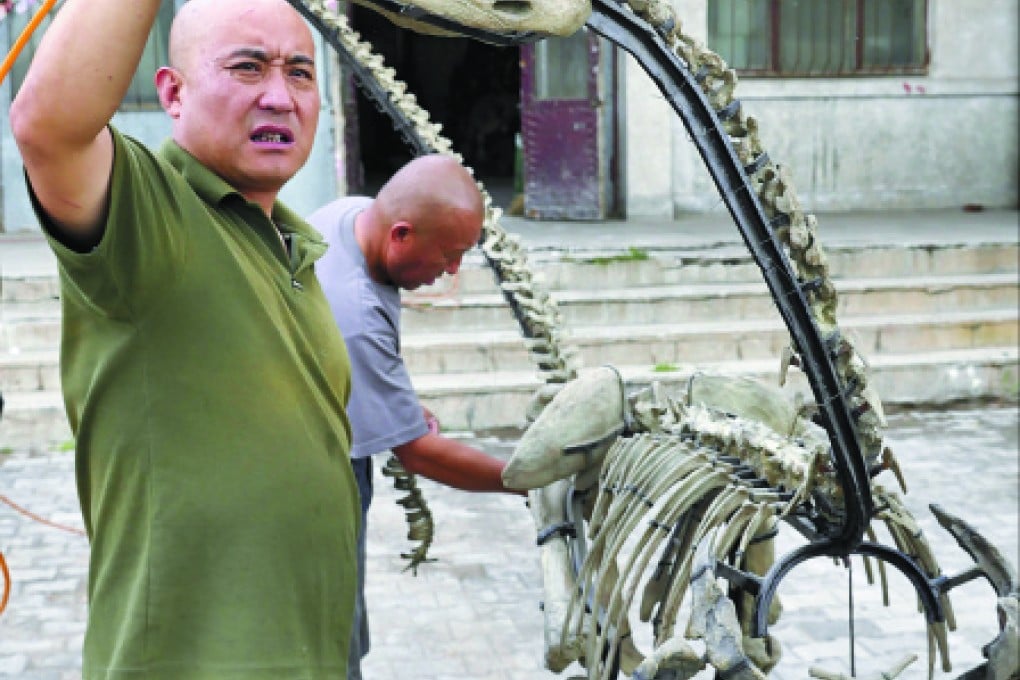

Sometimes the desert gives up larger treasures; a leg bone here, a rib there. When big fossils are found, technicians take over the site, covering the specimen and the ground that holds it in plaster and burlap. Once the cast is dry, they heave it into the back of a truck and take it away for closer study.

No fossil is insignificant: these days, a small piece of bone rich with diagnostic features could be enough to confirm a new species.