Lessons for US politicians in Nobel winners' efficient markets theories

Congressmen would do well to study Nobel trio's work on efficient markets and grasp how their own actions make them inefficient

The irony could not have been more jarring.

As the world waited with bated breath while American politicians decided whether to tip the United States into debt default, three American economists were jointly awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics.

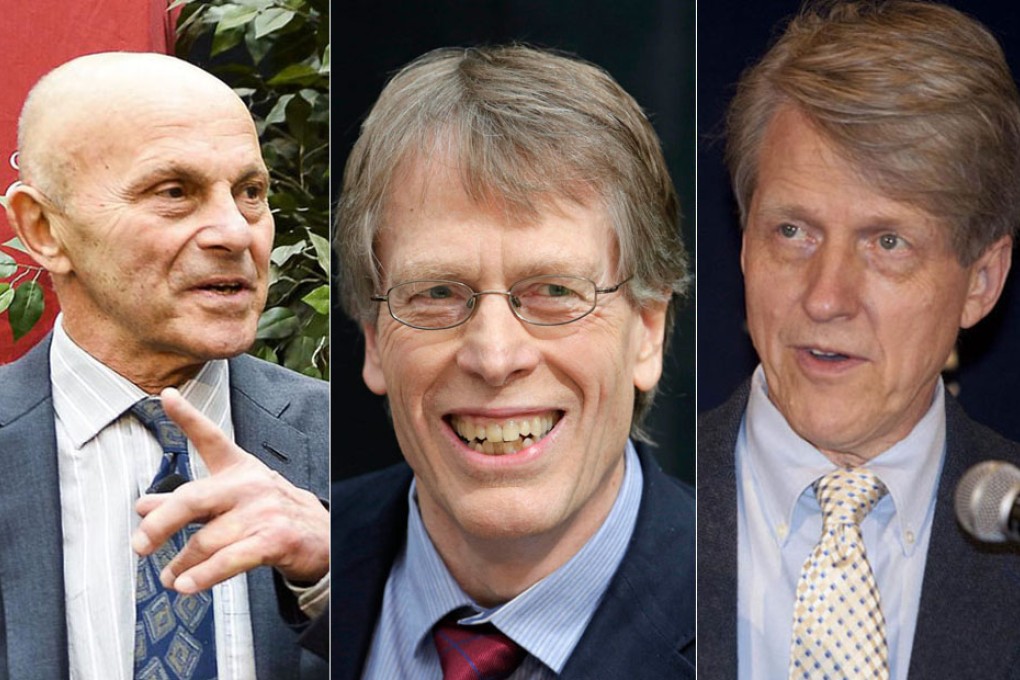

Eugene Fama and Lars Peter Hansen of the University of Chicago and Robert Shiller of Yale University "laid the foundation for the current understanding of asset prices", the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said. Their achievements were in developing new methods for studying how assets such as stocks and bonds are priced and how financial markets work.

While the new US laureates were being lauded for their research on asset price fluctuations, the US government was in serious danger of defaulting, potentially destabilising the entire global financial system.

Irony aside, however, the political conflict in Washington reflects in a way the competing theories of two of the Nobel winners. Fama and Shiller painted two diametrically opposing pictures of the financial markets, just as the struggle in Congress illustrates polarities in the functioning of government: is it based on the ideal of institutional processes with checks and balances managed by rational individuals, or is it subject to real-world chaos with those individuals acting irrationally at times?

Fama is best known for his investigation into and description of how the financial markets would work in a world of perfect efficiency. Using highly complex mathematics, his seminal work focuses on his hypothesis that there is an efficient market and the behaviour of stock prices in such a market. In an efficient market, all participants act rationally, with access to all the available information. Any activity or information that affects a company will be immediately digested by the market, resulting in an adjustment of its stock price. Hence the stock price reflects the true intrinsic value of the company, and its movements are merely random fluctuations around this intrinsic value. By analysing extensive historical stock price data, he concluded that price movements in the past and the present - the fundamentals - do not provide any guidance to a company's stock price in the short term.