Star Trek’s George Takei on his life’s mission: to tell his Japanese-American story as often as he can

- ‘I consider it my mission in life to educate Americans,’ says the Star Trek actor on the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II in camps

- He has a new picture book for children out about the years he spent interned as a child and the unfairness of being ‘seen as different from other Americans’

The incarceration of 120,000 Japanese-Americans, including children, labelled enemies during World War II is an historical experience that has traumatised, and galvanised, the Japanese-American community over the decades.

For George Takei, who portrayed Hikaru Sulu aboard the USS Enterprise in Star Trek, it is a story he is determined to keep telling every opportunity he has.

“I consider it my mission in life to educate Americans on this chapter of American history,” he says.

He fears the lesson about the failure of US democracy has not really been learned, even today, including among Japanese-Americans.

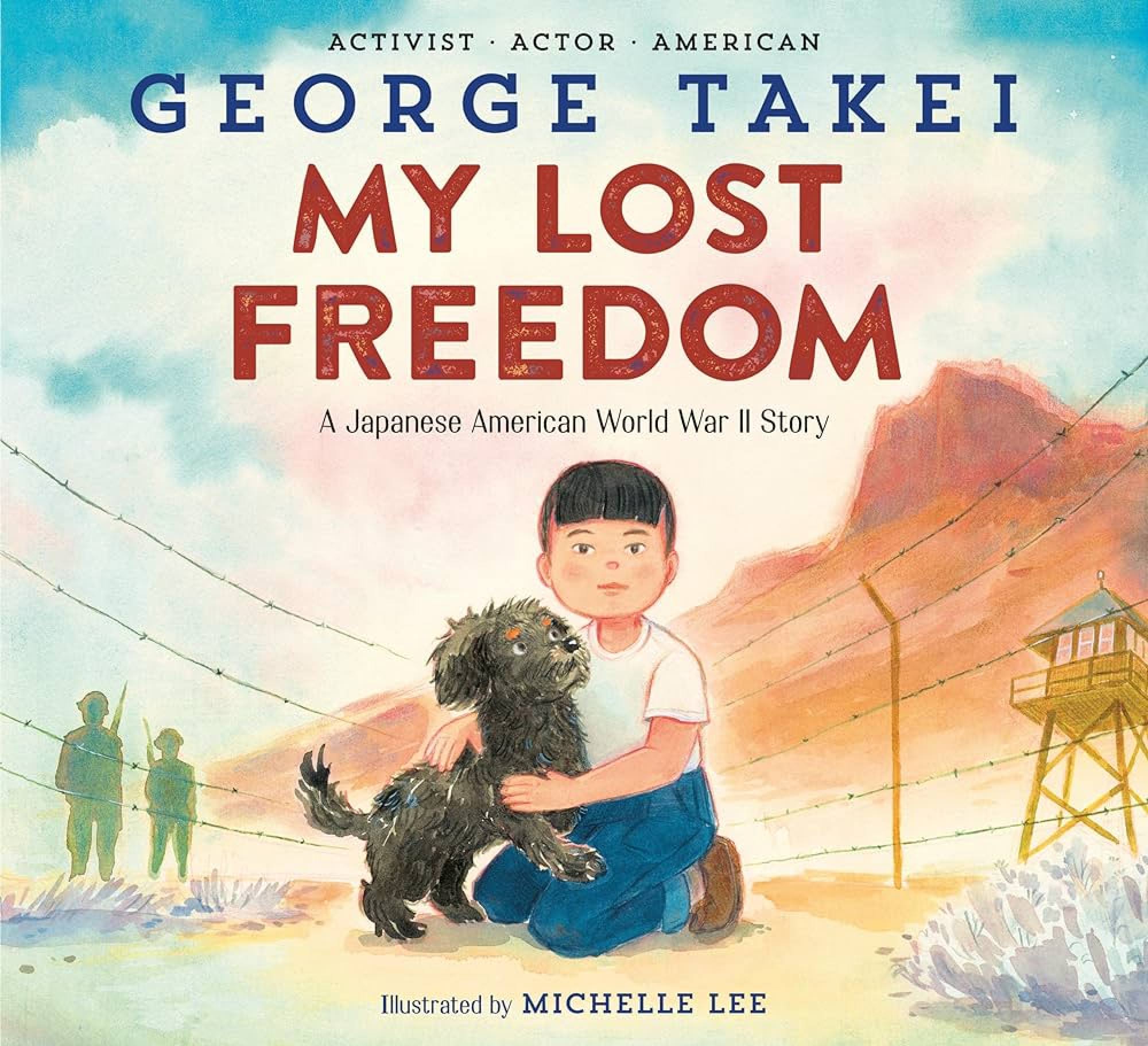

Takei, 87, has a new picture book out for children ages six to nine and their parents, called My Lost Freedom. It is illustrated in soft watercolours by Michelle Lee.

Takei spent the next three years behind barbed wire, guarded by soldiers with guns, in three camps.

“We were seen as different from other Americans. This was unfair. We were Americans, who had nothing to do with Pearl Harbour. Yet we were imprisoned behind barbed wires,” Takei writes in the book.

David Inoue, executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League, believes the message of Takei’s book remains relevant.

“One of the important things about having books like this is that it humanises us. It tells stories about us that show we’re just like any other family. We like to play baseball. We have pets,” Inoue says.

After Japan surrendered, Takei and his family, like all Japanese-Americans freed from the camps, were each given US$25 and a one-way ticket to anywhere in the US. Takei’s family chose to start all over again in Los Angeles.

In 1988, the Civil Liberties Act – after years of effort and testimonies by Japanese-Americans, including Takei – granted redress of US$20,000 and a formal presidential apology to every surviving US citizen or legal resident immigrant of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during the second world war.

Takei’s voice becomes choked when he recalls how his father did not live to see it.

He notes with pride the diversity depicted in Star Trek, a television series that started in the mid-1960s and developed a devout following.

“Different people, different ideas, different taste, different food. He wanted to make that statement. Each of the characters was supposed to represent a part of this planet,” the actor says.

Takei recalls that his father taught him how the government “of the people, by the people and for the people”, as Abraham Lincoln, the 16th US president, put it in a speech delivered during the American civil war, could also prove a weakness.

“All people are fallible, even a great president like Roosevelt. He got stampeded by the hysteria of the time, the racism of the time. And he signed Executive Order 9066,” Takei says.