Cheaper university education doesn't guarantee a degree

Most US high schoolers from affluent backgrounds will finish college; few from poor backgrounds will join them. Scholarship funds have increased enrolments dramatically, but there is still more work to do

Here is one solution to the rising cost of college: make it free. That's what a group of anonymous donors in Kalamazoo, in the US state of Michigan, accomplished a decade ago for students. Almost every high school graduate in the town is eligible for a scholarship covering from two-thirds up to the entire cost of in-state college tuition.

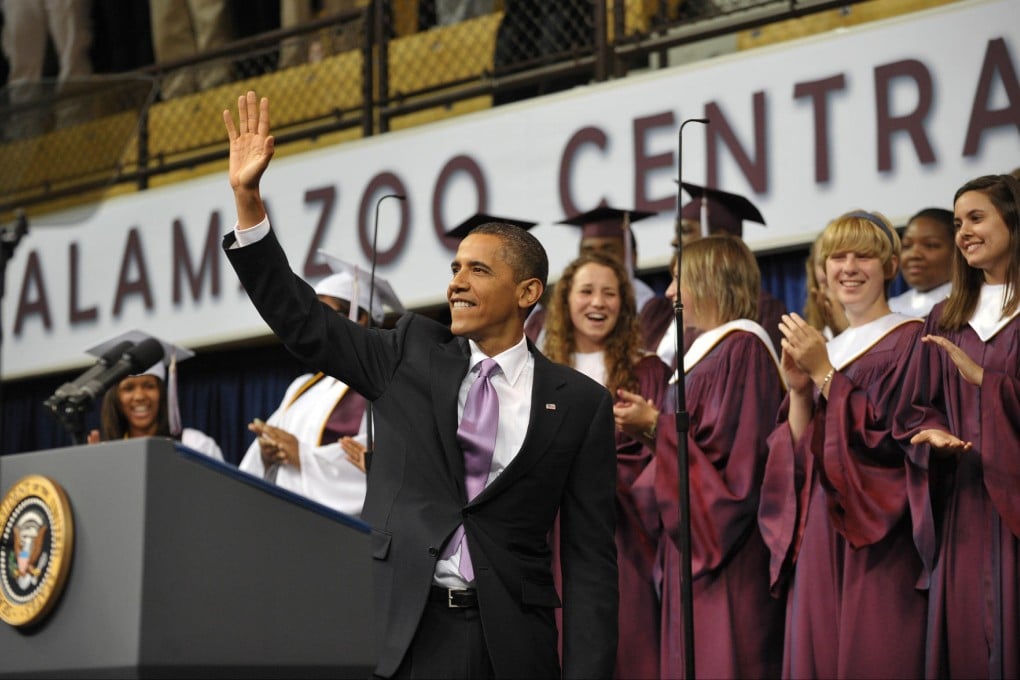

President Obama is just one of many who praised the so-called Kalamazoo Promise, flying to the city five years ago to speak at the Kalamazoo Central High School graduation. More than 35 cities, from Denver and Pittsburgh to Ventura and Long Beach, California, have since adopted their own versions of the Promise. These schemes vary. Some have minimum GPA requirements, or target only low-income students. But they share the goal of bringing college within financial reach for all.

For good or ill, a college education is steadily becoming an entry requirement for the American middle class. But not everyone has the same chance of securing a bachelor's degree. Most high schoolers from affluent backgrounds will finish college; few from poor backgrounds will join them. At the moment, the US college system serves to reinforce inequality over the generations, rather than reduce it. Can the Promise programmes help create a more level playing field? The Kalamazoo programme is now mature enough to provide some useful data. As always, there is good news and bad news.

First the good: high school graduation rates have shot up, and almost 90 per cent of Kalamazoo high school seniors are enrolling in college, compared to about 70 per cent for the state. Most encouraging of all, low-income and black high school graduates are almost as likely to enrol in college as their affluent and white peers. In fact, the black/white gap in college enrolment rates has completely disappeared in Kalamazoo, according to research from Timothy Ready at Western Michigan University.

Now for the bad news: gaps in race and income re-emerge when it comes to gaining a post-secondary qualification. The Promise has lifted college completion rates, but quite modestly, and far from equally.

Take the Kalamazoo high school class of 2006: white students were twice as likely as black students to earn at least 24 credits, and twice as likely to end up with a four-year degree (54 per cent against 26 per cent).