Advertisement

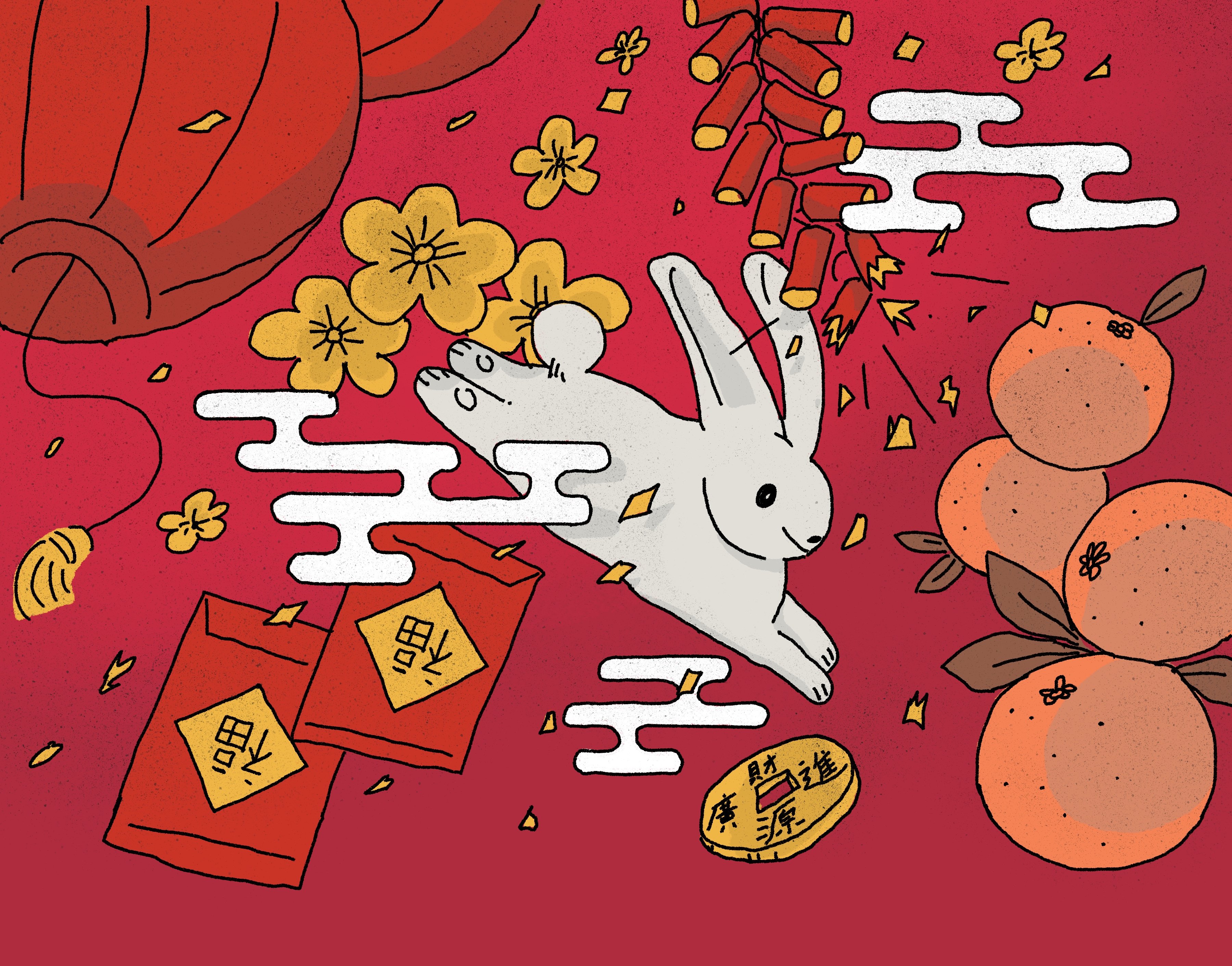

5 Chinese Lunar New Year traditions we rarely observe, from not showering to letting the mess pile up

- Lunar New Year traditions such as giving envelopes with ‘lucky money’ are still observed, but other Chinese folk customs have been largely abandoned

- Among them are things like not showering or cleaning the house for a few days in case we wash and sweep away the coming year’s good luck, and staying at home

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

4

It is not the end of the world if that “new year, new me” fantasy did not become a reality at the start of 2023, nor is there a need to wait 365 days to do it over – the Lunar New Year is just around the corner.

Observed by numerous cultures around the world, the Lunar New Year – also known as the Chinese New Year and Spring Festival – falls on January 22 this year.

The occasion marks the beginning of the year based on sun and moon cycles, and the return of spring after winter. This was especially important for farmers in ancient China, who relied on weather predictions to maximise their harvests and secure their livelihoods for the months to come.

While many around the world celebrate the Lunar New Year with traditions – in Chinese societies these include giving lai see paper envelopes filled with “lucky money” and snacking on melon seeds to represent a bountiful harvest – there are other folk customs that we have largely abandoned in modern times.

1. Making the Kitchen God happy

Chinese legend has it the Kitchen God, or Stove God, visits each household (just like Santa Claus) during the 12th month of the lunar year and reports back to the Jade Emperor in the sky on what everyone has been up to in the past year.

Advertisement