The mysterious Russian wife of Chiang Kai-shek son and former Taiwan leader Chiang Ching-kuo

- Factory worker Faina Vakhreva married Chiang Ching-kuo, son of China’s Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, in 1935, propelling her into China’s first family

- Little was known about her until author Mark O’Neill started researching her life. He has now written her biography

In a photograph taken in the mid-1930s, a young woman in a striped swimsuit sits in the shallows of a river near the Russian city of Sverdlovsk, which reverted to its original name of Ekaterinburg in the 1990s.

Hers was an extraordinary life – a Russian factory worker propelled from a life in the Soviet Union under Stalin to a member of China’s first family. Later, during the communist revolution in China, she and her husband fled to Taiwan where, under martial law, Chiang Ching-kuo would succeed his father as leader of the Republic of China.

“Her whole life was about adjusting, about completely changing who she was,” says writer and China analyst Mark O’Neill, who has written her biography, China’s Russian Princess: The Silent Wife of Chiang Ching-kuo, published by Joint Publishing in Chinese and English.

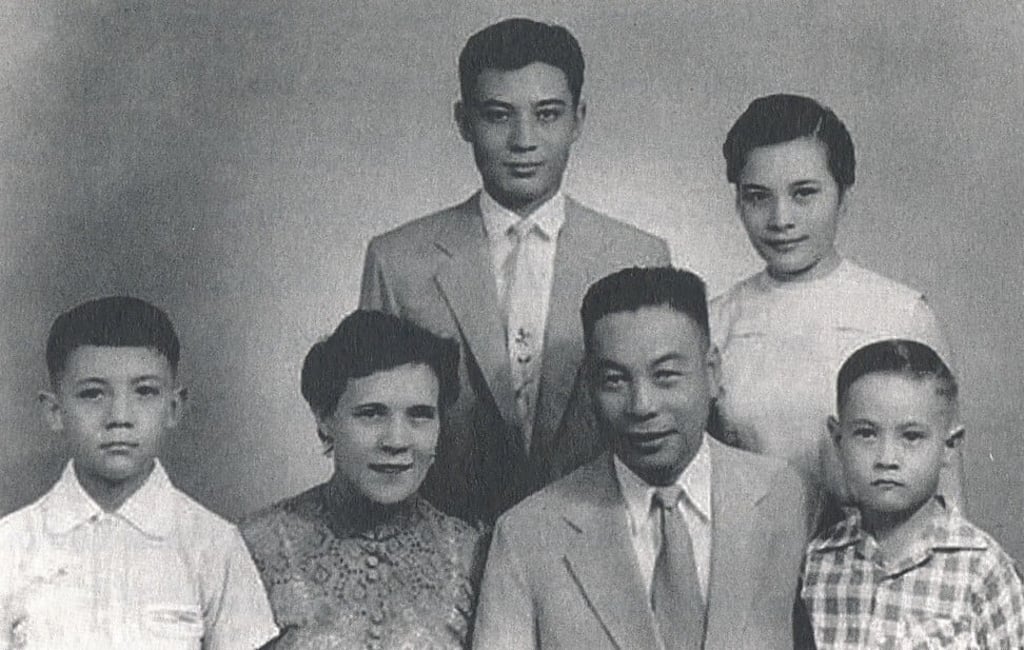

It is an empathetic portrait of a woman whose life was never easy. An orphan born into poverty and hardship in East Belarus in 1916, she would have four children, three of whom – her three sons – would die before her. While her life had all the trappings of privilege and power, she appears to have been happiest as a frugal housewife.

By telling her life story, O’Neill also paints a picture of Soviet Russia and Stalin’s Kafkaesque policies that made Chiang Ching-kuo a political prisoner in the Soviet Union for years before his life continued in China.