Why art hidden from Japanese on eve of Hong Kong invasion in World War II, and never seen again, still fascinates after 80 years

- Some 300 paintings, drawings and maps collected by Hong Kong businessman Sir Paul Chater went missing when the Japanese Army occupied Hong Kong in 1941

- Some paintings were stripped from their frames, placed in sealed tins and buried in the garden of Government House, but searches have not turned them up

Works of art depicting coastal China from the 17th to the 19th century comprise what the Hong Kong Museum of Art describes as one of its most legendary collections.

The collection could have been much bigger. More than 300 paintings, drawings and maps went missing when the Imperial Japanese Army occupied Hong Kong during World War II, and their whereabouts remains one of Asia’s biggest unsolved art mysteries.

The collection was owned by Indian-born Armenian businessman Sir Paul Chater, who arrived in Hong Kong in 1864 and made a fortune in trade and real estate. His name is commemorated by local landmarks including Chater Road and Chater Garden in the Central business district.

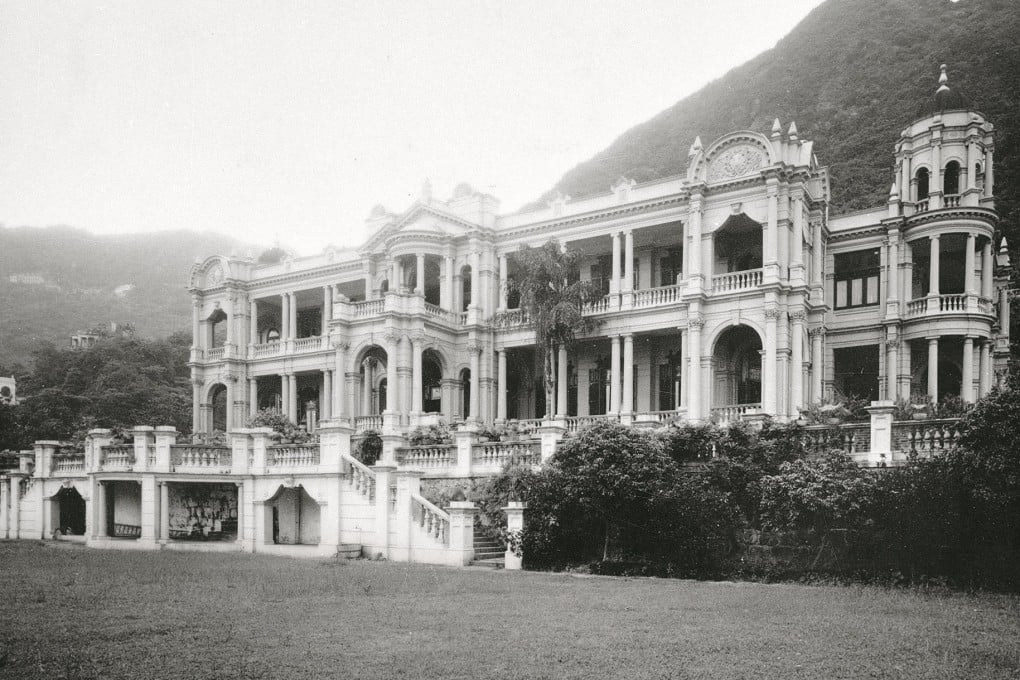

Following his death in May, 1926, his unrivalled collection of some 430 works that had decorated the family’s palatial Marble Hall residence in Conduit Road, Mid-Levels, was bequeathed to the Hong Kong government. It was handed over in 1935, when Lady Chater died and Marble Hall was emptied of its valuables, according to Liz Chater, a descendant of the businessman and an authority on the family’s history.

“My thought is that Sir Paul probably hoped his legacy might stimulate the government to create a museum,” says Chater, speaking from her home in Southampton, southern England.

If that was his dream, it came true in 1962 when the remaining items formed one of the founding collections of the Hong Kong Museum of Art. An exhibition at the museum in Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, “Lost and Found: Guardians of the Chater Collection”, runs until November – once the museum reopens after the coronavirus emergency is over – and attempts to get to the bottom of the mystery.