How China’s ‘one-child generation’ got trapped in the population pyramid

China’s one-child policy has created a zero-sibling generation – and caring for parents and children in a tough economy is taking its toll

Wendy Liu has grown to dread the sound of her phone.

These days, most calls mean a parent of the 47-year-old vocational school teacher has been rushed to the hospital. Whether her mother with Alzheimer’s disease or her father with cancer, any emergency means a long, anxious drive from work to her home in Guangzhou – a stress-ridden trip she has made on countless nights.

Liu and her husband Deng Jie are members of China’s first generation of only children. Born in 1977 – only a year after the country instituted a one-child limit for most urban households – they not only have to raise two children, but also care for four ageing parents.

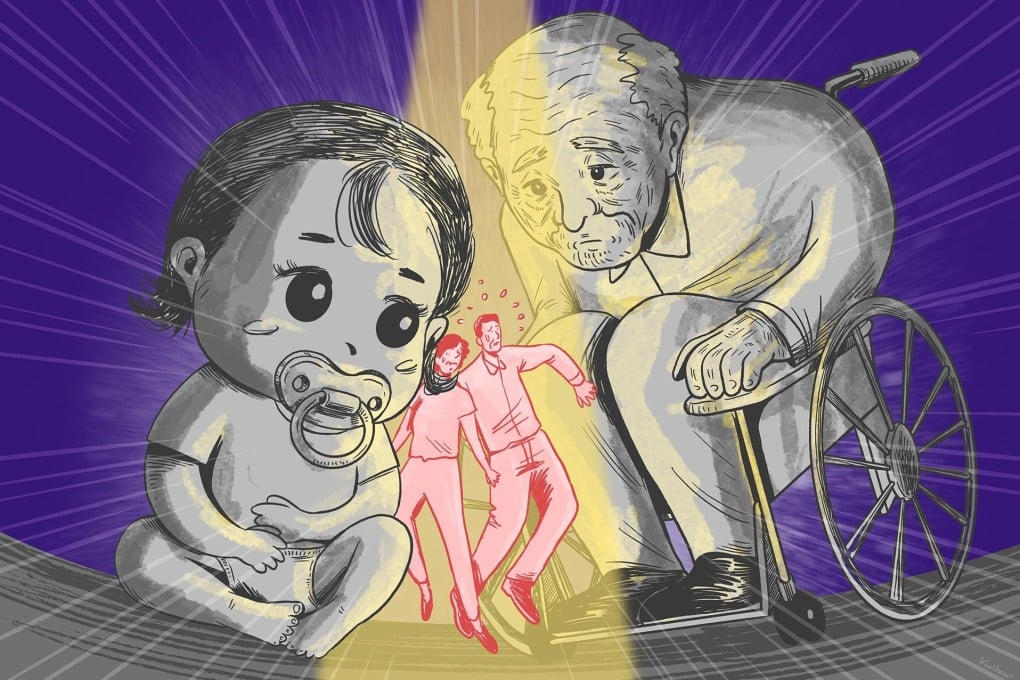

The dilemma of balancing care for the elderly and the young is becoming more commonplace as this cohort enters middle age. This “sandwich generation” is being overwhelmed with threefold pressures: a longer life expectancy for their elderly parents, extended dependency periods for their children, and hurdles in their own careers compounded by an economic downturn.

Raised without any siblings in the 1980s, China’s first batch of only children were once jokingly called “little emperors” for being the sole focus of their families.