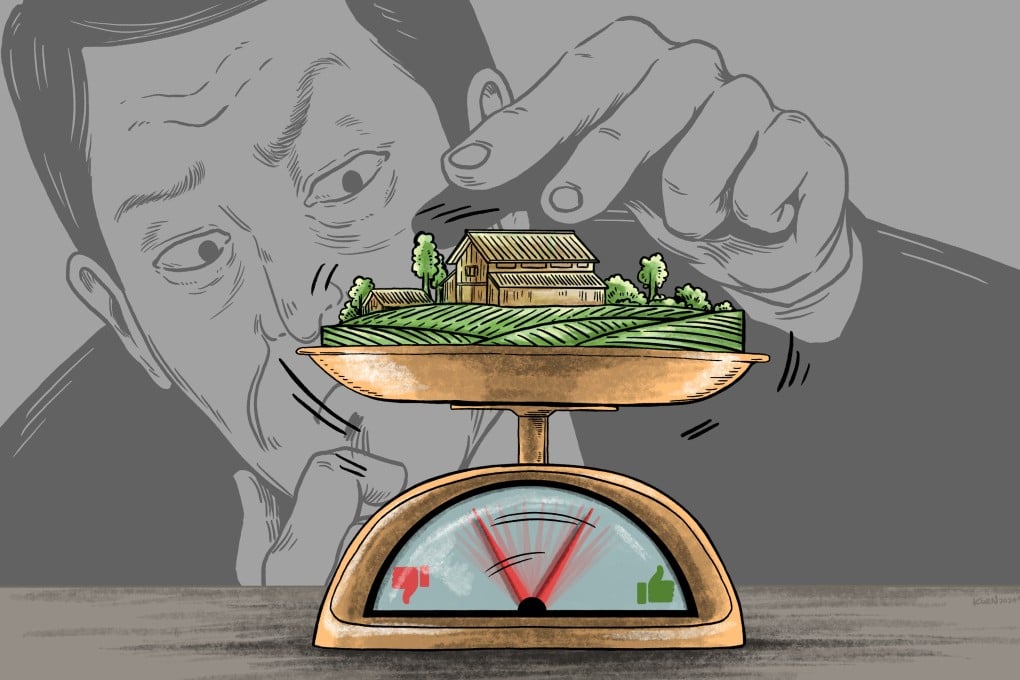

China’s rural land is vast, vacant – and not for sale. Would putting it on the market spell windfall or woe?

- China’s rural land, unlike urban property, remains closed to sales by individuals, foreclosing a potential source of economic activity

- Debate rages over whether to open that land up to the market, with arguments against saying it would remove farmers’ main source of stability

Under an unassuming WeChat profile, “Baishun Farmer’s Property”, Zhang Ming provides updates on a large and growing market. Through this account, he shares details of new village houses in suburban Shanghai that are up for sale – a real estate listings board, unexceptional in most of the world.

Not so in China. Personal transactions of rural homes are strictly forbidden under the rules of property ownership. But at any given time, Zhang has information on over 400 houses scattered across the outskirts of the metropolis.

“Most of the owners have moved downtown and have no plans to go back, so they need to cash out,” said the property agent.

But researchers and former officials continue to advocate for the legalisation of such transactions, an action which would herald a new era for rural land reform for the country and have profound implications for its future.

China has gone through three rounds of land reform since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. The most recent, in 1978, allowed collectively owned land to be contracted by individual households.

If rural land is made tradeable, I believe it can push the Chinese economy back to an annual growth rate of more than 8 per cent