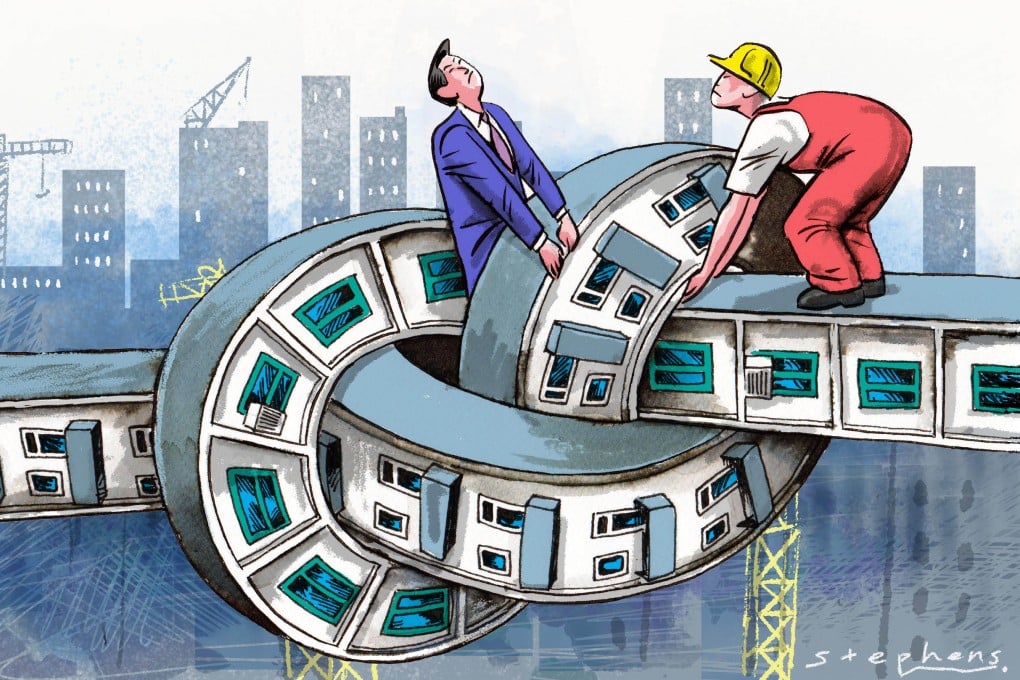

Opinion | How Hong Kong can untangle the Gordian knot of public housing

- The pandemic is an obvious scapegoat, but the government’s failure to keep the waiting time for a public housing flat down to three years predates the arrival of Covid-19

- Instead, we should look to the many rounds of consultations, redesigns and developer disputes to understand why waiting times have increased in recent years

This involves around 2,300 flats, constituting just 11 per cent of all delayed flats – far less than the 87 per cent “affected by the inclement weather” and the 66 per cent “affected by unforeseen geological conditions”. This proves that the pandemic is merely a scapegoat.

As the saying goes, “the tree falls not at the first stroke”. The Housing Authority’s pledge of a three-year public rental housing waiting time was already broken in 2015. Since then, the waiting time has almost doubled. This dire situation can be attributed to constant delays. An overview of the construction programmes of the last eight years shows that on average, 15 per cent of public housing projects were delayed each year.

The known delays are just the tip of the iceberg. Currently, the government only discloses information about projects to be completed in the first five years of the coming 10-year period. Delays already occur annually within those five years, even when the construction earmarked accounts for only one-third of the total production of the 10-year period. It can be safely assumed, therefore, that the problem will be even more severe in the second five-year period.