Opinion | Why fixing inequality is central to China’s common prosperity goal

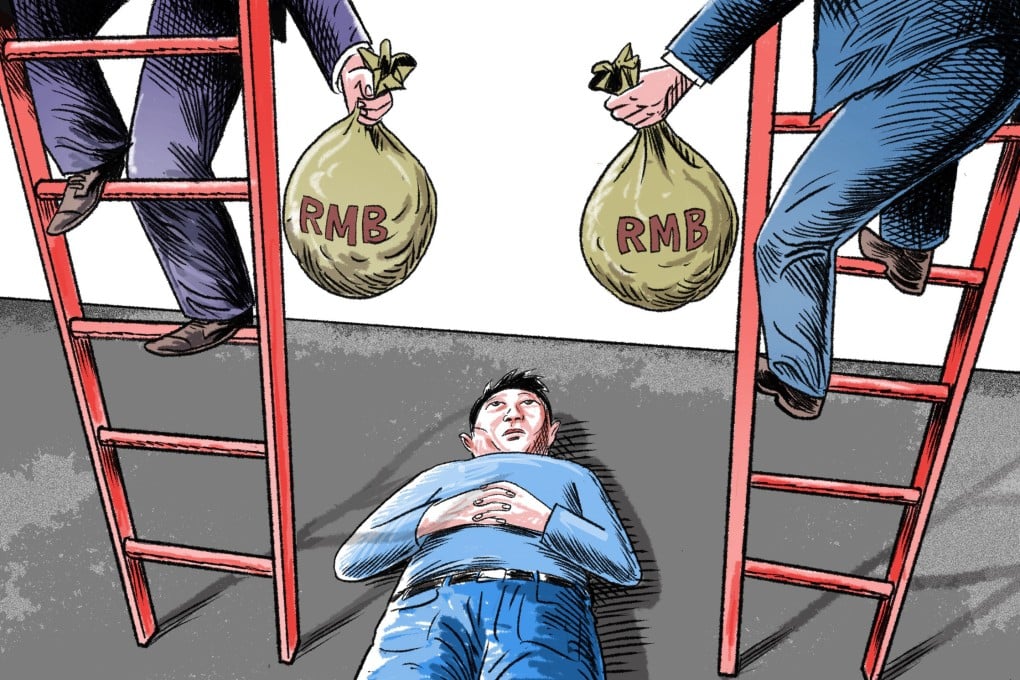

- China must urgently deal with the issue of the country’s wealth inequality as letting it fester could put the goal of achieving common prosperity in danger and undermine faith in the government among the impoverished and young people who lack hope for the future

Last month, Panzhihua, a city in western China’s Sichuan province, announced this would be its “breakthrough” year in establishing itself as a common prosperity pilot zone. It is following the example of Zhejiang province in the east, another such pilot zone which was set up in 2021. The idea is to push for a high-quality development that focuses on closing the economic gap between regions, between urban and rural areas, and in income.

The concept of common prosperity is not new. It first appeared in 1953 during the Mao era as he pushed China towards socialist collectivisation.

Since 1978, some people and regions have indeed become rich. China has transformed from one of the world’s poorest countries to its second-largest economy, and from a relatively equal society to one of the most unequal in the world.