Advertisement

Opinion | Why so many young Chinese are depressed – and how Beijing can help

- The rise of youth depression owes much to China’s rigid education system, the loneliness of only children and tight rural-urban migration restrictions

- Centrally planned schooling, along with migration restrictions that mean millions of children are left behind in rural areas, should be done away with

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

3

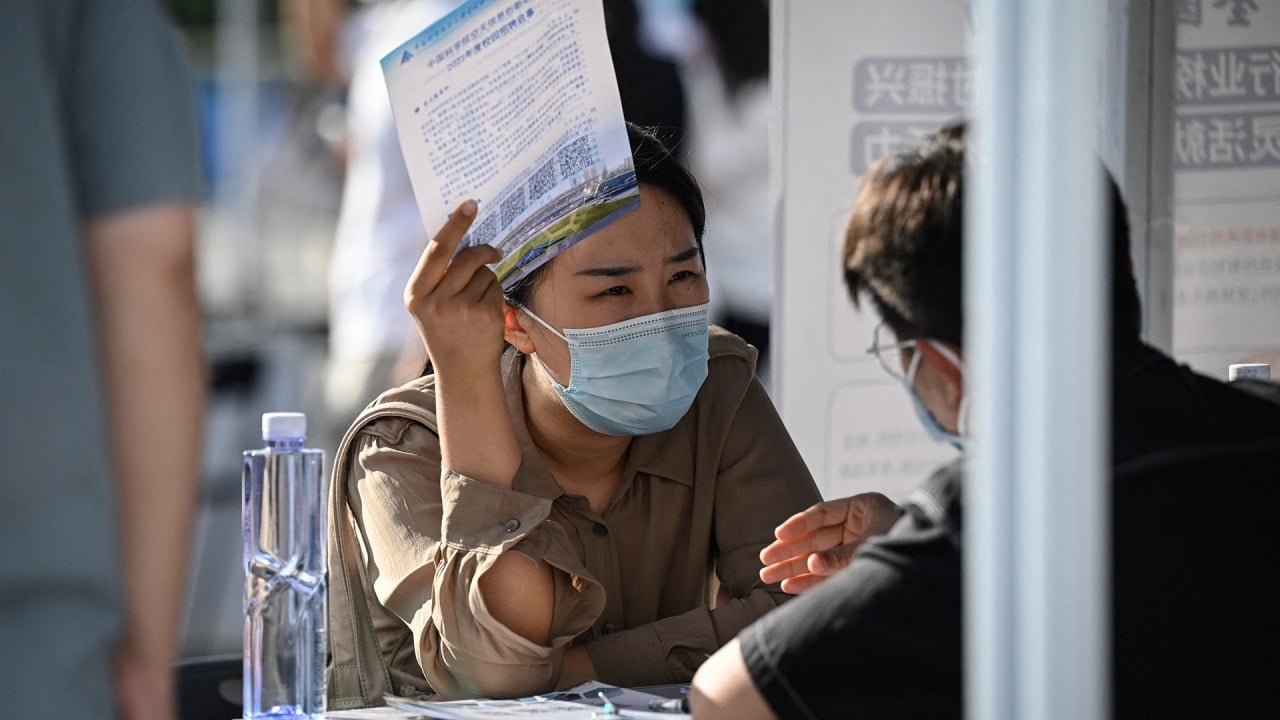

China’s high youth unemployment rate and increasingly disillusioned young people – many of whom are “giving up” on work – have attracted much attention from global media outlets and Chinese policymakers. The standard narrative is to associate the problem with the country’s recent growth slowdown. In fact, the issue goes much deeper.

The rise of youth depression has been decades in the making, and owes much to China’s rigid education system, past fertility policies and tight migration restrictions. Chinese youth are burned out from spending their childhood and adolescence engaged in ceaseless, intense study. Attending a good university is seen as necessary for securing a good job; and for rural children, a university degree is the only path to legal residence in cities under the hukou registration system.

As if the pressure to get into a university wasn’t bad enough, the rigid structure of the school system makes matters worse. After nine years of compulsory schooling, children must pass an exam to enter an academic high school, and only 50 per cent of them are allowed to pass. Teenagers who don’t make the cut attend vocational high school and are destined for low-paying jobs.

Chinese children therefore begin studying in earnest very early in life. They not only go to school but also receive expensive outside tutoring and pursue extracurriculars like music or chess – which are rewarded in an opaque manner. In an attempt to alleviate some of these pressures, the government banned for-profit tutoring and barred public-school teachers from offering such services on the side. But this only added more pressure, because the price of tutors increased as their supply declined.

Wealthy households in Shanghai and Beijing now pay US$120 to US$400 per hour for in-person tutoring, while the children of the non-wealthy must study even harder to make up for the tutoring that their parents can no longer afford. In the 1980s and 1990s, Chinese village and city streets were full of children. Today, one rarely sees any unless it is a holiday. Even on weekend afternoons, playgrounds are empty. The kids are all inside studying.

Another cause of youth depression is loneliness. Owing to the one-child policy, which lasted from 1979 to 2016, children in urban areas lack siblings. And unlike the first generation of single children after the policy was introduced, later generations do not even have cousins with whom to play (since their parents have no siblings, either). One survey of Chinese college students finds that the typical only child is more likely to experience anxiety and depression than classmates with siblings. Suicide rates for children between the ages of five and 14 have increased since 2010.

Advertisement