Opinion | Why a property crash could be good for China

- The wealth redistribution would benefit ordinary families, boost consumption and rebalance the economy

- China needs more sustainable economic growth and, crucially, it has the tools to minimise the short-term pain needed to achieve this

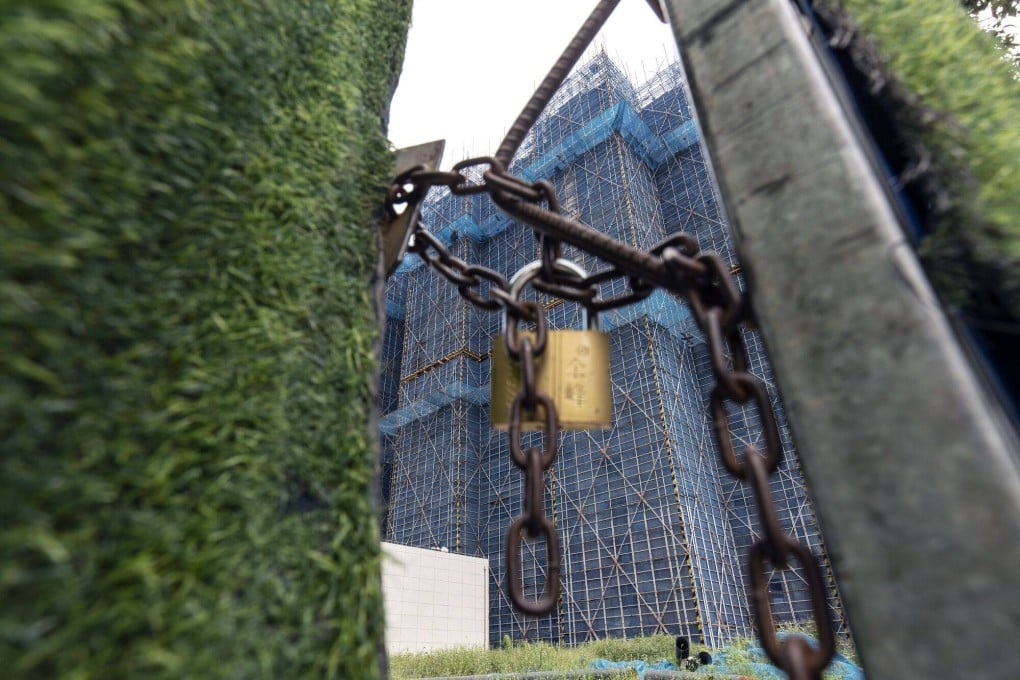

Despite property prices across China struggling to recover, the day of reckoning has yet to come for the sector. However, participants and onlookers must ask whether there is any benefit to delaying a correction.

In Shanghai, a city with a per capita gross domestic product of about US$25,000 last year, the average property price per square metre is US$18,400. In comparison, the average price in New York is just US$16,500, against a much higher GDP per capita of over US$100,000. This stark difference in housing affordability underscores the distortions and imbalances in China’s real estate market and its broader economy.

This results from the unequal distribution of income generated by GDP. Ordinary households, which should allocate most of their income to consumption rather than savings, retain too small a share of the national GDP. Meanwhile, businesses, local governments and wealthy households claim an oversized portion of GDP, leading to a significantly elevated rate of savings and investment.