Advertisement

Opinion | Little hope of progress on US-China military talks when two sides remain so far apart

- Even with better communications between their respective militaries, the trust gap between Beijing and Washington is unlikely to improve

- US calls for military transparency might sound reasonable, but they favour the more powerful nation and come from a side failing to practise what it preaches

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

26

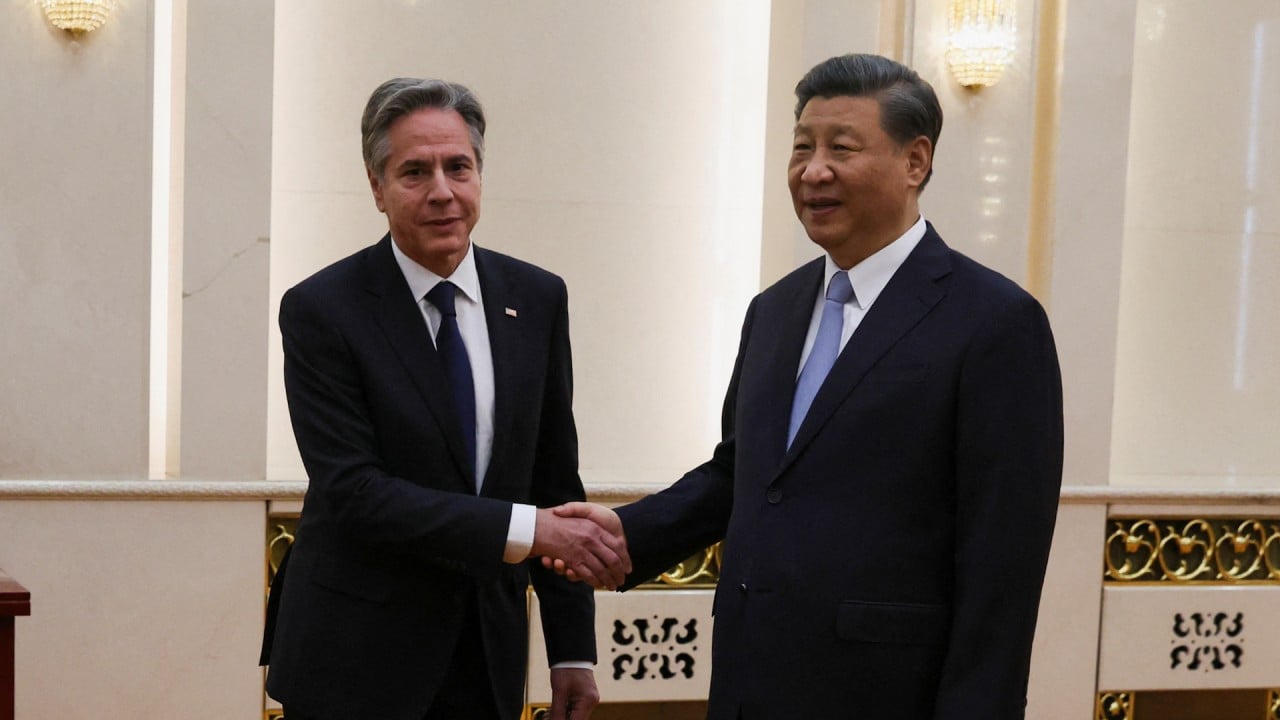

The main purpose of US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s recent visit to China was, in his words, to help reduce “misunderstandings and miscommunications” so as to prevent incidents between the two sides. He was unsuccessful in restarting military-to-military talks, though, and it seems that just agreeing to talk has become politicised while the communications process is being used to the advantage of one side or the other.

The level of US-China military communications is at a nadir, and incidents between their militaries are increasing in frequency and intensity. As these incidents proliferate, a growing chorus of policymakers and analysts is calling for better communication before things get out of control.

Tensions remain high. There was a near-collision in the Taiwan Strait on June 3 when a Chinese warship abruptly cut across the bow of a US warship. That incident came after a May 31 incident when a Chinese fighter jet forced a US reconnaissance place in international airspace to fly through its wake turbulence. US defence officials have described these incidents as part of a pattern of more aggressive behaviour by China.

The US wants to reestablish communications to help tamp down the possibility of conflict, but China is not cooperating. As pointed out by Yun Sun, a senior fellow and co-director of the East Asia Programme and director of the China Programme at the Stimson Centre, its position on restarting military dialogue might be part of a strategy that encompasses the communication process.

At the very least, it seems to have been captured by their fundamental differences. With the heavy US interest in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and other hotspots around the globe, Beijing might think Washington is more averse to conflict than it is. That means China thinks it has more diplomatic space to manoeuvre and could also think that agreeing to communicate will undermine its tactic of brinkmanship.

Moreover, China might want to keep the US guessing as to its intent and red lines, whose crossing may trigger military conflict. At the most extreme, China might even believe that a crisis would provide an opportunity to extract concessions from the US and negotiate a regime of peaceful coexistence.

Advertisement