Advertisement

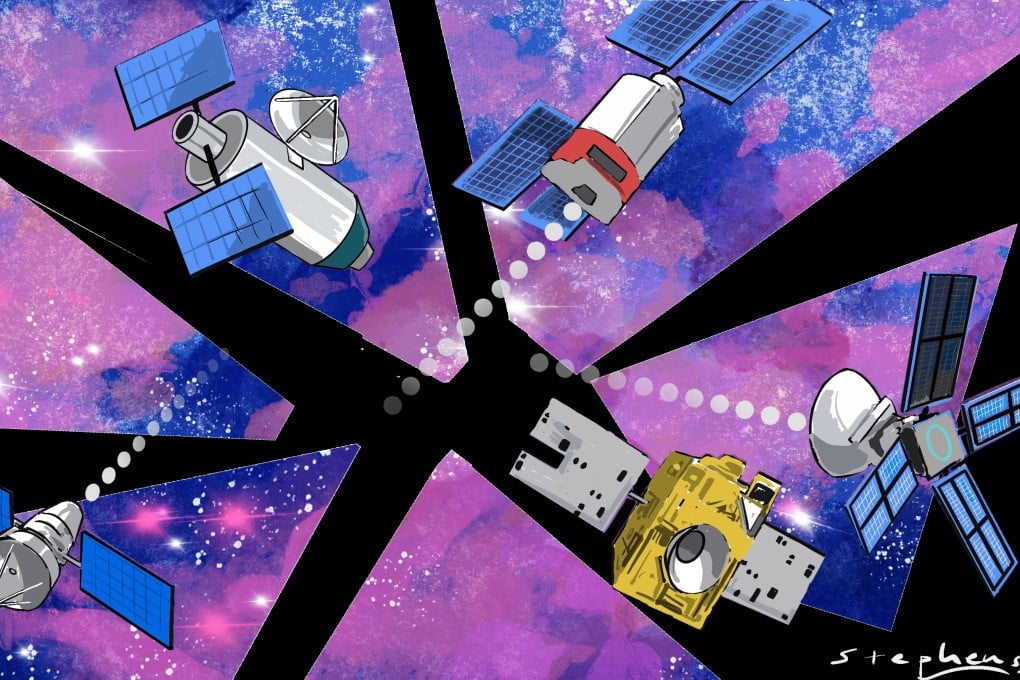

Opinion | US-China rivalry should not mean giving up on a global space framework

- With the US and China each forging their own space agreements with friendly states, perhaps common ground could be found in, for example, clearing up hazardous space debris

- While separate agreements obviate the need for international norms, they also establish principles and structures that could form the basis of a new global treaty

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

2

Conflict between the West and China is spilling over into attempts to overhaul the Outer Space Treaty, which began governing the use of space in the 1960s when the United States and Soviet Union raced to be first on the moon.

Those tensions and broader geopolitical conflicts are dimming the prospects of a new global framework any time soon to address the surge in the use of space for national security, commercial ventures and communications by the more than 80 countries that own satellites.

The recent plenary of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space revealed West-China divisions on issues that include ownership of resources mined from celestial bodies, accessing the troposphere (the atmosphere’s lowest layer) and beyond for national security purposes, cleaning up space debris, and managing safety in the launch, orbit and decommissioning of spacecraft. North-South frictions cut across these issues too.

There have been sharp words elsewhere. Last month, a top US military official said Washington had “no choice” but to prepare for conflict in space given Russia’s attack on Ukraine and China’s plans to dominate space by mid-century. Weeks before, the head of Nasa warned the US and China were in a “space race” and backed the existing restrictions on cooperation. He had cautioned in January that “we better watch out”.

The European Space Agency said in January it was no longer planning to send astronauts to China’s Tiangong space station, citing budgetary and political reasons. In March, the European Commission said the European Union must expand efforts “to defend the EU’s strategic interests and to deter hostile activities in and from space”, singling out China’s development of “extensive space programmes and counterspace capabilities” as a concern. Nato recently declared space an “operational domain”.

Meanwhile, there have been developments from China. In January, a Hong Kong-based firm, which also has operations in mainland China, signed a US$1 billion deal with Djibouti to build a launch facility in cooperation with a company owned by an Africa-focused Chinese investor. Some see this as China escaping its treaty obligations since the African country is not a signatory to the Outer Space Treaty. Others counter that the agreement is customary international law.

Advertisement