Advertisement

Macroscope | Is China back? That will require more than just a reversal of recent policies

- China’s leadership has announced major policy U-turns that have left global investors and other observers bullish about its economic future

- But correcting policy errors is no substitute for the reforms needed to deliver robust growth, including a return to political pragmatism and honest feedback

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

16

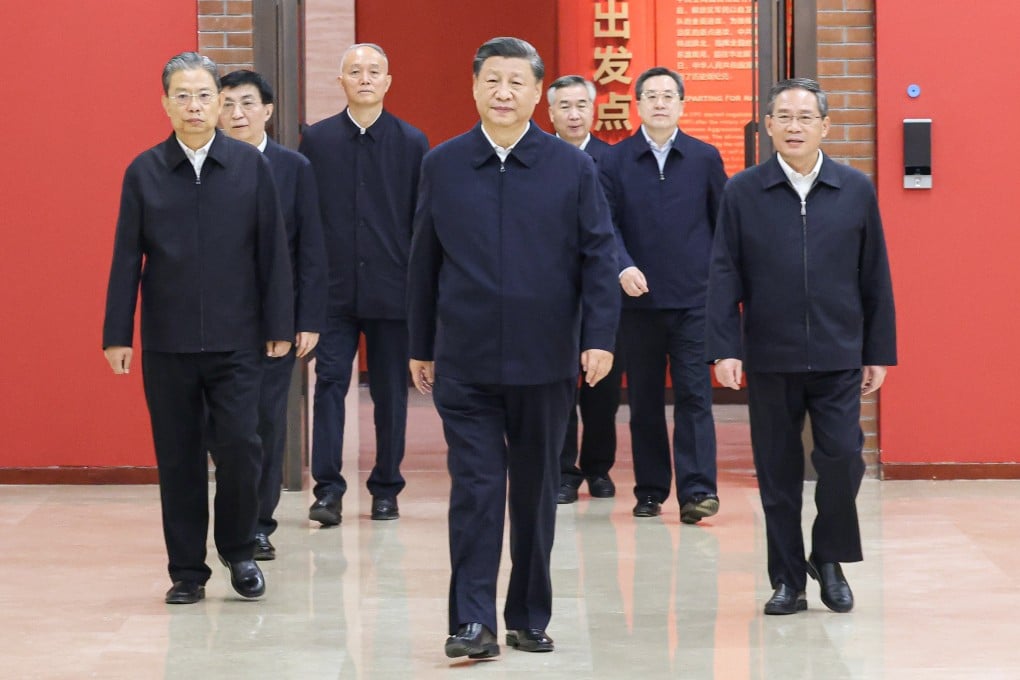

When US President Joe Biden took office in 2021, his first message to the rest of the world was: “America is back.” Having assumed his third term as general secretary of the Communist Party in October, President Xi Jinping appears to be issuing a similar proclamation.

Advertisement

In the past two months, China’s leadership has announced or signalled a series of major policy reversals, abruptly ending nearly three years of severe “zero-Covid” restrictions, easing the crackdown on tech companies and the real-estate sector, reaffirming its commitment to economic growth and extending an olive branch to the United States at the Group of 20 summit. With the world’s second-largest economy apparently reopening its doors for business, investors are reacting with enthusiasm.

But while China’s pro-business reset bodes well for international trade and global peace and stability, putting the Chinese economy on the right track will require more than just a reversal of recent policies. What is really needed is bringing pragmatism and honest feedback back into the political system. As I showed in my book, How China Escaped the Poverty Trap, these attributes defined China’s adaptive governance during the Deng Xiaoping era.

There is a common misperception that the “China model” means top-down control by a strong, authoritarian government, flanked by muscular state enterprises. In fact, 30 years of poverty and suffering under Mao Zedong proved that the combination of top-down planning, state ownership and political repression was a recipe for failure.

That is why Deng introduced a hybrid system that I call “directed improvisation”. The Communist Party remained firmly in power, but the central government delegated authority to numerous local authorities across China and liberated private entrepreneurs from state controls.

Advertisement

Playing the part of a director rather than a dictator, the government in Beijing defined national goals and established appropriate incentives and rules. Meanwhile, lower-level authorities and private-sector players improvised local solutions to local problems.

Advertisement