Advertisement

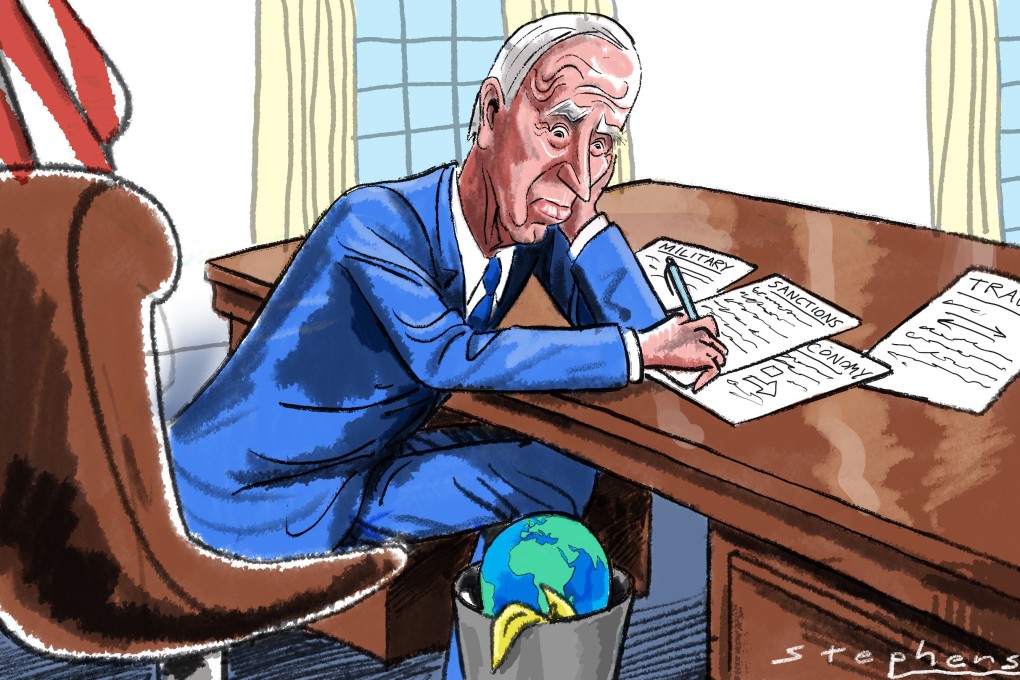

Opinion | Joe Biden made 2022 the year of democracy vs autocracy, but the battle played out in no one’s favour

- Attempts by the US to isolate rivals like China and Russia while reasserting its global leadership have led to protectionism in trade and questionable defence ties

- The US should conversely be championing economic globalisation while being tougher on military partners who fail to uphold democratic values

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

10

Close to the end of 2021, US President Joe Biden hosted his flagship Summit for Democracy in an effort to re-establish the US as a leader of democracy worldwide. Through much of the year that followed, policymakers and political leaders in the West saw the world as a battleground between democracy and autocracy.

Advertisement

That world view was accentuated by crises both at home and abroad. Early in the year, Russia invaded Ukraine. Tensions then escalated across the Taiwan Strait. In March, an Australian journalist was detained by China on charges of spying, not long before Canberra accused Beijing of political interference. And in December, Germany uncovered a plot to overthrow its government, involving – among others – a Russian national.

In recent years, the US and its allies have employed economic sanctions and decoupling tactics extensively to coerce sundry rivals and alleged forces of illiberalism around the world. Sanctions were used twice as frequently in the 1990s and 2000s as they were during the period from 1950 to 1985. That frequency doubled again in the 2010s, according to historian Nicholas Mulder.

That is now being combined with selectivity in economic ties. In October, Canada’s deputy prime minister, Chrystia Freeland, argued that democracies should come together to “build our supply chains through each other’s economies” and reduce exposure to undemocratic states – a concept otherwise known as “friendshoring”.

Yet, far from forcing geopolitical rivals or authoritarian regimes to change course, these policies have merely reversed the gains of globalisation. From 2001 to 2008, world trade nearly tripled from around US$6 trillion to over US$16 trillion, according to data from the World Trade Organization. Then, after the global recession, trade largely remained flat. In 2019, before the pandemic began, world trade still hovered around US$19 trillion.

Advertisement

As a result of this stagnation, the global economic pie has not expanded fast enough for most countries. Growth prospects now stand diminished, especially in the developing world, and populism has consequently surged everywhere.

Advertisement