Opinion | Hongkongers in the UK championing the cause back home can speak for themselves, thank you

- Foreign governments, organisations and activists should not assume for themselves the mantle of white saviours in defence of human rights, democracy and rule of law in Hong Kong

Being gay and childless, I have been able to travel around the world for extended periods of time and try to listen to, understand and learn from peoples whose countries have undergone similarly traumatic political and social transformations. In the past four months, I was in South Africa and Namibia, which are still adapting to legacies of decades-long apartheid.

A highlight of my visit was the varied responses I got when conversing with a group of young white Namibians about their sense of allegiance and belonging. As I shared my perspectives as a Hongkonger, one of them said Hongkongers did not deserve universal suffrage. The Namibian considered Hong Kong too small and insignificant, even though his country, with a population of 2.5 million, fought a war of independence with South Africa that lasted 23 years and seven months.

In London, I have, from time to time, received heartfelt expressions of support and solidarity from complete strangers. One aspect of my lived experience as a Hong Kong émigré has nevertheless stood out.

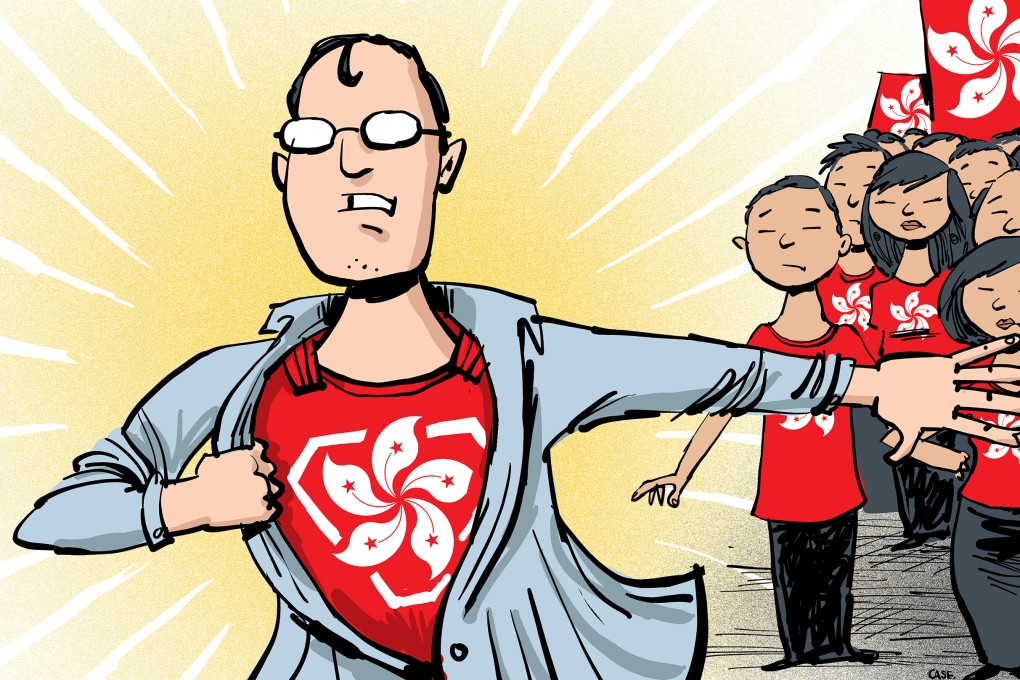

At assemblies Hongkongers in London are expected to attend as a matter of duty and conscience, invariably almost all Hongkongers are masked and keep quiet for fear of being identified, while white Hong Kong Watch activists take centre stage to tell us about the demise of Hong Kong, as if we needed to be lectured about what happened to our home.