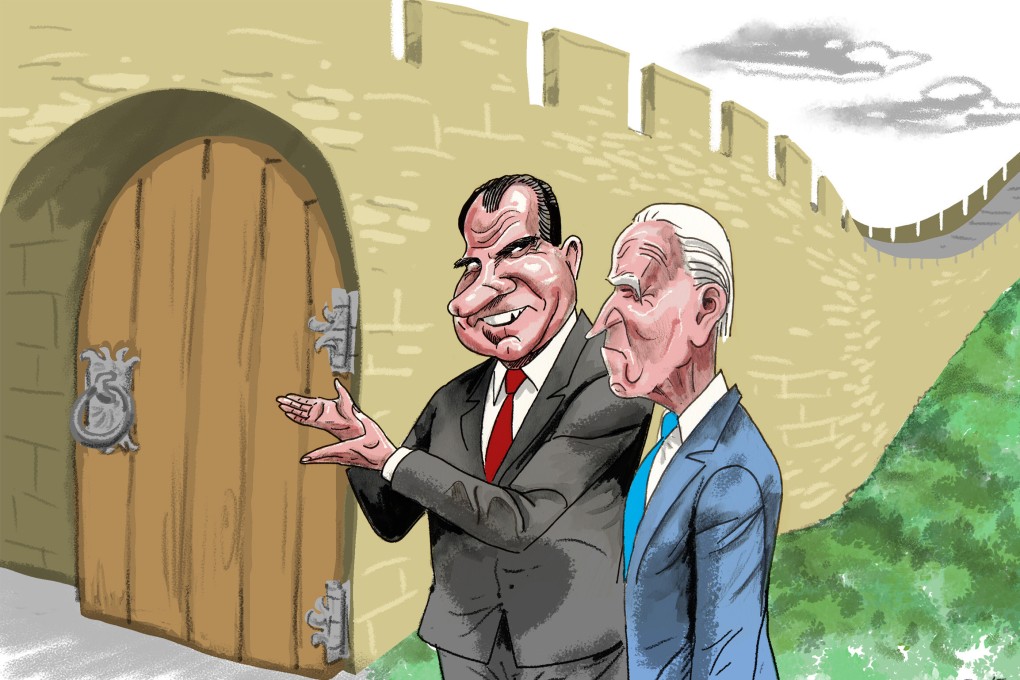

Opinion | 50 years after Nixon’s historic trip, US-China relations can be brought back from the brink

- Ever since Nixon’s visit in 1972, the US has hoped China’s rise would bring about its liberalisation; now disappointed, Washington has begun a contest with no clear outcome

- Yet the 50th anniversary of that historic trip should serve as a timely reminder that competitors need not become enemies if it serves their interests

Richard Nixon may never be considered a great American leader, being the only president to resign from office, following the Watergate scandal. The legacies he left, however, are not easily forgotten: China, China, China – that is, his landmark visit to China in “the week that changed the world” in 1972; an opera titled Nixon in China; and the phrase “only Nixon could go to China”, now used to describe a political leader’s unique ability to accomplish something particularly daunting or taboo.

Fifty years after Nixon’s visit, the world is unrecognisable. China, now the world’s second-largest economy, is no longer a place where “a billion of its potentially most able people … live in angry isolation”, as Nixon wrote in 1967.

What marked Nixon’s presidency was his exceptional vision and audacity, or more precisely, vision-inspired audacity on China policy. When relations between the Soviet Union and China reached a nadir as a result of border clashes between the two, Nixon sent private word to the Chinese that he desired closer relations.

When Mao Zedong invited American table tennis players to visit China, Nixon took the message of goodwill and sent his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, to conduct a visit in secret, bypassing cabinet officials. The trip, made without informing Japan – America’s key regional ally in the region – caused the “Nixon shock” in Japan.

These feats of great daring were the result of a grandmaster’s exact calculations on the chessboard of international politics. In those days, the main preoccupation for Washington was Soviet expansionism. Therefore, it was in America’s best interests to embrace “Red China”.