Advertisement

Opinion | The maths behind Britain’s Huawei U-turn and pivot to the Indo-Pacific

- There is an upside for Britain in working more closely with its traditional allies – the US, Australia and Japan – in the region. Free-trade agreements with all three countries all hang in the balance

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

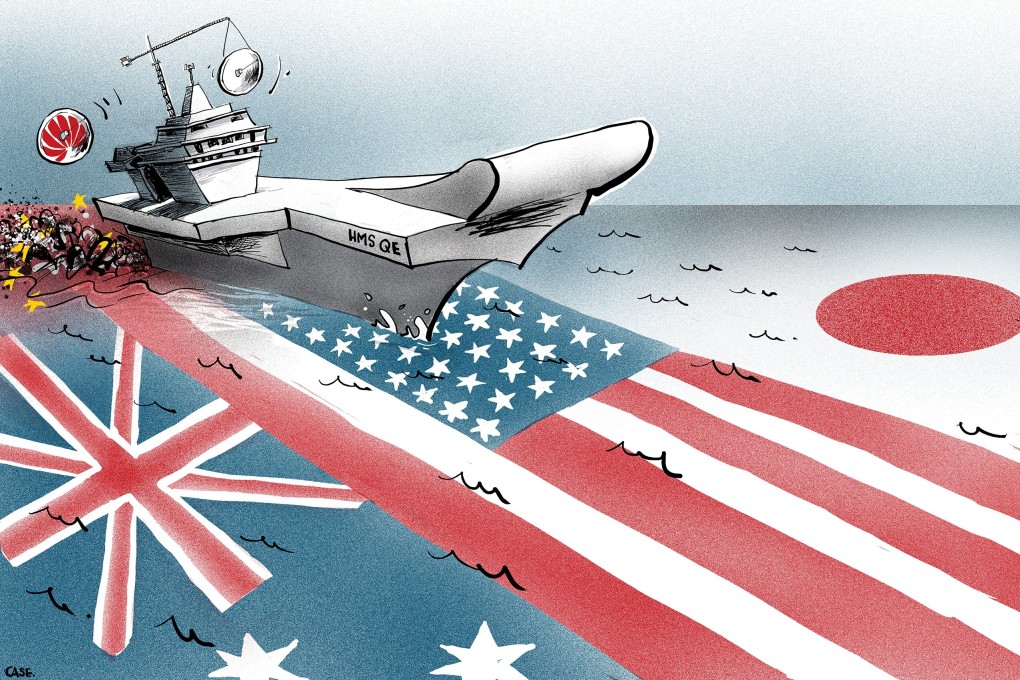

While the British government’s decision to scrap Huawei’s role in the country’s 5G infrastructure has dominated Sino-British relations in the past week, it is the news of the upcoming deployment of the Royal Navy’s aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth to East Asia that perhaps matters most in terms of Britain’s future in the region.

Advertisement

Britain has repeatedly emphasised the importance of the Asia-Pacific to its plans for trade following Brexit. It is no coincidence that the region is home to three of the four of the countries that Britain is currently negotiating free- trade agreements with: Japan, Australia and New Zealand. The fourth country is the United States. Britain has also announced its intention to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Britain’s ambitions are not just commercial. Its military presence in the Indo-Pacific has been minimal at best since 1971, when, the Hong Kong and Brunei garrisons aside, it withdrew most of its forces from East of Suez. Since the 1997 handover of Hong Kong, there have been scant British forces in the region.

But in the last few years this has started to change. A British Defence Staff for Asia-Pacific has been established in Singapore; the Five Power defence pact between Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia and Singapore has been refreshed; and the Royal Navy has sent a number of ships to conduct freedom of navigation patrols through the region, including the South China Sea.

None of this has gone unnoticed by Beijing.

05:22

Huawei founder on cybersecurity and maintaining key component supply chains under US sanctions

Huawei founder on cybersecurity and maintaining key component supply chains under US sanctions

The “golden age” of Sino-British relations that former British prime minister David Cameron tried to create has now entered the deep freeze, thanks to a number of high profile clashes in recent months. Hong Kong has been a particular point of friction, but there have been others: for example, the British government’s project to diversify away from the Chinese supply chain in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Advertisement