Advertisement

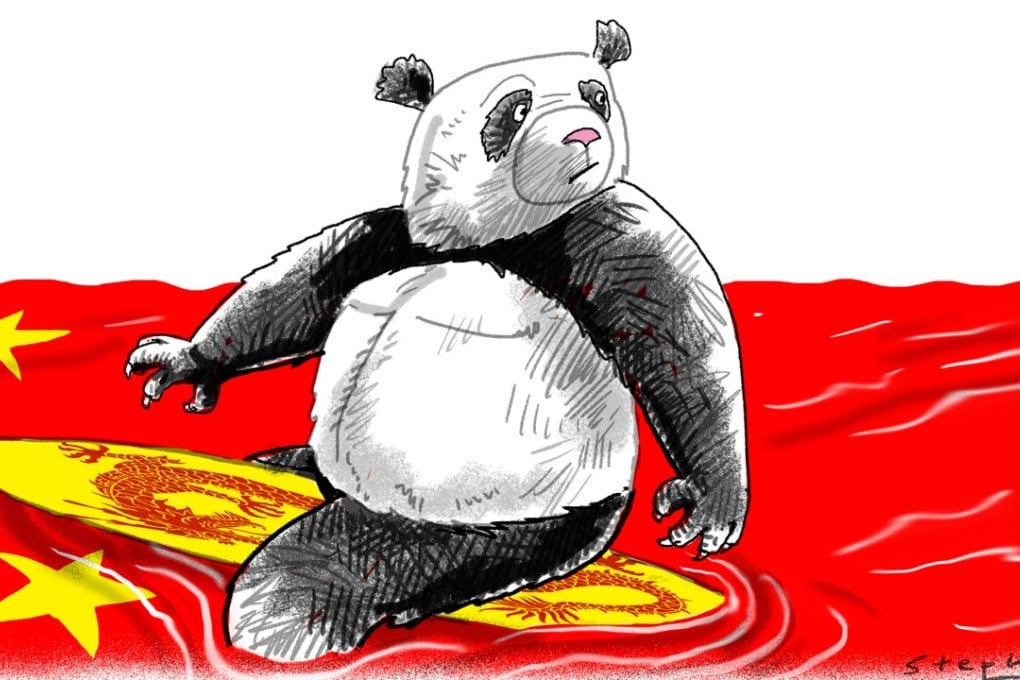

Xi Jinping has consolidated power, but China is still waiting for the promised waves of reform

David Zweig says Xi Jinping has secured his power base, but the expected market-oriented reform programme has not materialised and is not likely to in the near future

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Many critics around the world have decried the recent lifting of term limits on the Chinese presidency, asserting that it reflects a hunger for more political power. Yet the pro-China camp, in Hong Kong and Beijing, argues that power begets change and that, without more centralised power, it would be impossible to get the bureaucracy to budge. Their explanation highlights President Xi Jinping’s selflessness as a leader for whom power is only a tool to reform China and reassert the country’s greatness by 2035.

Advertisement

Well, which is it: power for power’s sake, or power for social, economic and political reform?

Since 1978, major changes in leadership have predated major “waves of reform”, which were introduced at a national party congress (and the subsequent NPC) or at the third plenum of a new Central Committee, which usually follows the NPC meeting by about a year.

To succeed under Xi Jinping’s brand of socialism, the onus is on performance for the people

Thus, while Deng Xiaoping was rehabilitated in July 1977 at the 11th party congress, the new era of reform policies began with the third plenum in December 1978. Similar reform waves occurred in 1984-85 (the third plenum of the 12th Central Committee), 1987-88 (the 13th party congress), 1992-93 (the 14th party congress) and 1997-98 (15th party congress and subsequent NPC meeting). Each followed a major consolidation of power by one Communist Party faction, involving a set of policies cutting across economic sectors, a decimation of the bureaucratic administration, a strong demand for social and economic change from Chinese society and a global environment conducive to reform.

One story circulating in Hong Kong … is that Xi was disengaged from the drafting of the reform document that emerged from the third plenum of the 18th Central Committee

The last reform wave, in 1997-98, followed a consolidation of power by Jiang Zemin and his “Shanghai faction”. Bureaucrats who lost their jobs jumped into the “sea of business”. Unofficial privatisation shifted most small and medium-sized state-owned enterprises into private hands. A private housing market emerged, which has driven the economy ever since.

When Xi took the reins, China was in trouble. Massive corruption threatened the state’s legitimacy, overinvestment plagued the economy, people breathed putrefying air, drank appalling water and ate food from soil deeply permeated by chemicals. While perhaps well-meaning, the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao team had allowed these problems to fester. Many Chinese hoped for a new “wave”. Yet, by all previous standards, Xi, whose political team comprised leaders from different factions and earlier generations, lacked the heft to carry out a massive reform movement.

Surprisingly, Xi unveiled an unprecedented reform package at his first third plenum, the theme of which was the “decisive role” the market would now play in allocating resources. State-owned enterprises would be forced to function under real market conditions. The privatisation of rural land would allow peasants to use their land as collateral to open businesses in new towns to which they would be allowed to migrate. Legal reforms were predicated on ending party control over selecting and paying judges at the same territorial level, along with an intensified anti-corruption campaign. Improving the environment moved to the top of the agenda. Other market-oriented changes included hospital reform, greater opening to foreign investment, and retirement and unemployment programmes. All in all, the plan proposed 360 significant reforms to the Chinese economy and social policies.

It’s time for China’s annual economic check-up: what prescription can we expect from leaders?

Advertisement