Beijing’s ban on gatherings of foreigners in restaurants raises eyebrows, and questions

Philip J. Cunningham says Beijing’s ban on foreigners congregating in restaurants may be rooted in the fear that they could be a terrorist target, but clampdowns based on racial differences come across as intolerant

Any time authorities start setting up roadblocks to free movement and association based on racial identity, or just “differentness”, alarm bells start ringing, especially to Westerners who cannot and should not forget the horror of the master lesson provided by Nazi Germany. Growing up in a largely Jewish area of New York, I learned to be vigilant in the face of prejudice and intolerance, even in petty acts, and even in isolation. Working in China and Japan taught me that prejudice is real, but also imagined. It gets magnified by one’s minority status. Sometimes it is malevolent, sometimes inadvertent and unintended.

Holocaust survivor ‘understands’ Asian fetish for Nazi uniforms – but the underlying evil should never be forgotten

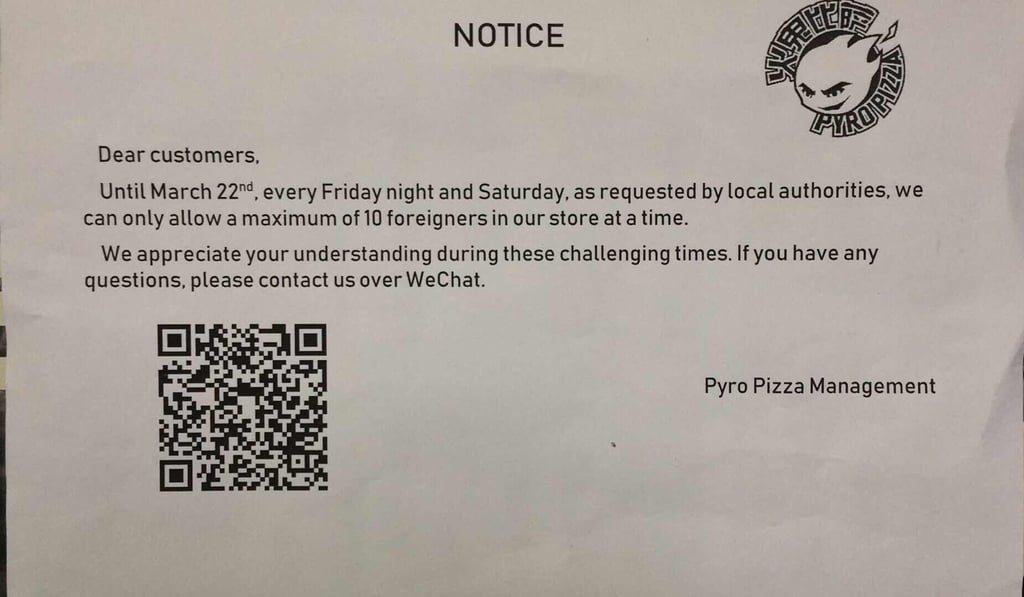

“Pizza-gate” is about as petty as a potentially disturbing crackdown can get. Only a handful of Beijing bar owners posted signs limiting foreigners and it was made clear it was for a short, designated time frame. But the damage was done, because foreigners in China, like elsewhere, are hypersensitive to exclusion. Foreigners in China often feel excluded, even under the most welcoming circumstances, if only because of the yawning gap of language, culture and social differences with the host country.

The clumsy edict proscribing attendance of “more than 10 foreigners” is the crux of problem. What is a foreigner in this context? Is the “security” measure directed primarily at Caucasians? Asians? Chinese holders of foreign passports? Why 10? Who’s counting? Who defines what foreign means?

Beijing subway passengers in foul-mouthed row over foreigner smoking on train

This sort of cyclical self-policing has a long history in China, but it might seem irrational or offensive to observers who see the law as a constant, not something that is over- or under-enforced according to whim.