A new era dawns for Xi Jinping’s China, but what will it mean for the rest of the world?

David Zweig says the Communist Party’s goal to build national power follows logically from its earlier focuses on national unity and wealth creation. But a political system that is ideologically driven and in the grip of an almost all-powerful leader could be a recipe for disaster

But what exactly do they mean by a “new era”? What are the common characteristics of these three eras and what can they tell us about China’s path forward?

The three eras share three common themes: first, opponents of the dominant leader must be removed from office, some through retirement, but others through purges; second, the party puts forward a new guiding ideology attributed to this one leader, which all party members must follow unquestionably and in a “unified” manner; and, third, China takes on a historic task, which all members must unswervingly seek to attain.

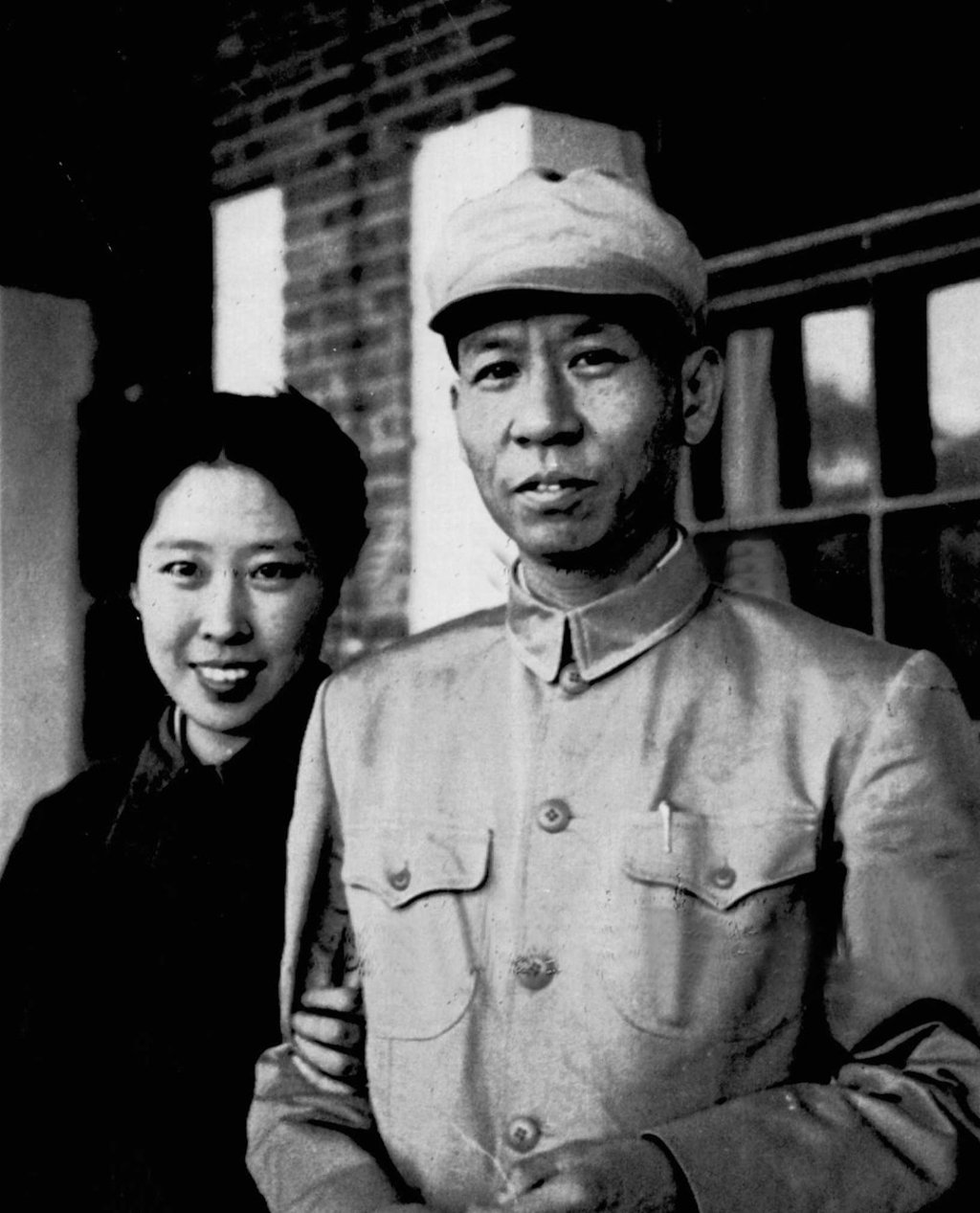

While many analysts see the first era starting in 1949, preparations for it actually began in Yan’an, the communist base in Shaanxi province where the party settled after the 1934-35 Long March. During the Rectification Campaign of 1942, all party members were forced into intensive study sessions to internalise the newly emerging Mao Zedong Thought, creating “unified thinking” within the party.