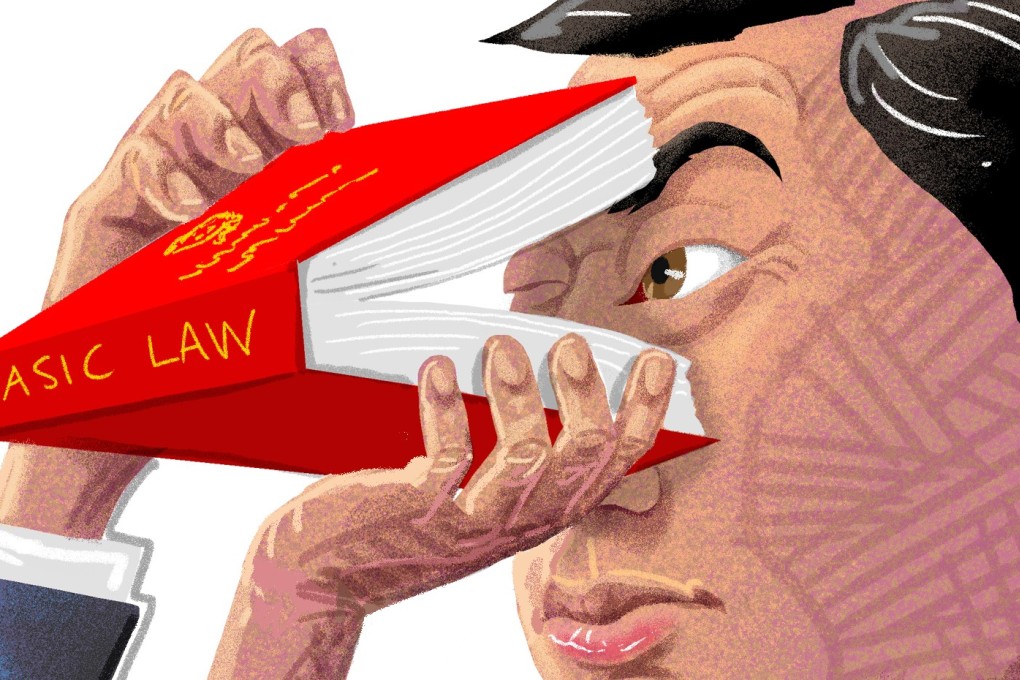

How Hong Kong’s Basic Law can serve the interests of all China

Simon Young says a narrow view of the Basic Law is partly to blame for the ‘one country’ versus ‘two systems’ deadlock in Hong Kong. It’s time to widen the perspective to see what the SAR can offer the country

However, the internal perspective has proven to be divisive, one that sees continuous tension and conflict between the “one country” and the “two systems”. The conflict is well known, if not tiresome. One sees it in recent speeches on the success or failure of the Basic Law.

It’s time to resolve conflicts over ‘one country, two systems’

The side trumpeting the “one country” hails the Basic Law’s first 20 years, pointing to Beijing’s restraint and the many ways in which Hong Kong has been allowed to prosper. To this group, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress has made “only” five interpretations of the Basic Law, each measured and made for good reasons. Those calling for independence or self-determination are regarded as ungrateful, spoiled, and soon to be, if not already are, enemies of the state unless stronger measures are taken.

Hong Kong’s handover anniversary is an opportunity to restore faith in ‘two systems’

Those trumpeting the “two systems” highlight the “high degree” of autonomy promised to Hong Kong in the Basic Law and the Sino-British Joint Declaration. To them, one Standing Committee interpretation is one too many, and the five we have had have seriously damaged common law judicial independence. What is there to celebrate when press freedom has been deteriorating, Chinese mainland authorities have increasingly encroached on Hong Kong’s autonomy, and the local government has been unable to defend Hong Kong’s interests. The government’s “hardline approach” is to blame for the failure of “one country, two systems”, and independence talk is but a natural consequence of the political reform void.

In the internal perspective, Hong Kong remains a ‘borrowed place on borrowed time’, with 2047 standing in the place of 1997