To Beijing, with love: please stay out of Hong Kong’s leadership race

Frank Ching imagines what the late Dorothy Liu, a fair-minded NPC delegate who had the trust of both Beijing and Hongkongers, would have told Chinese leaders, amid deep fears that the next Hong Kong chief executive will be a mere stooge

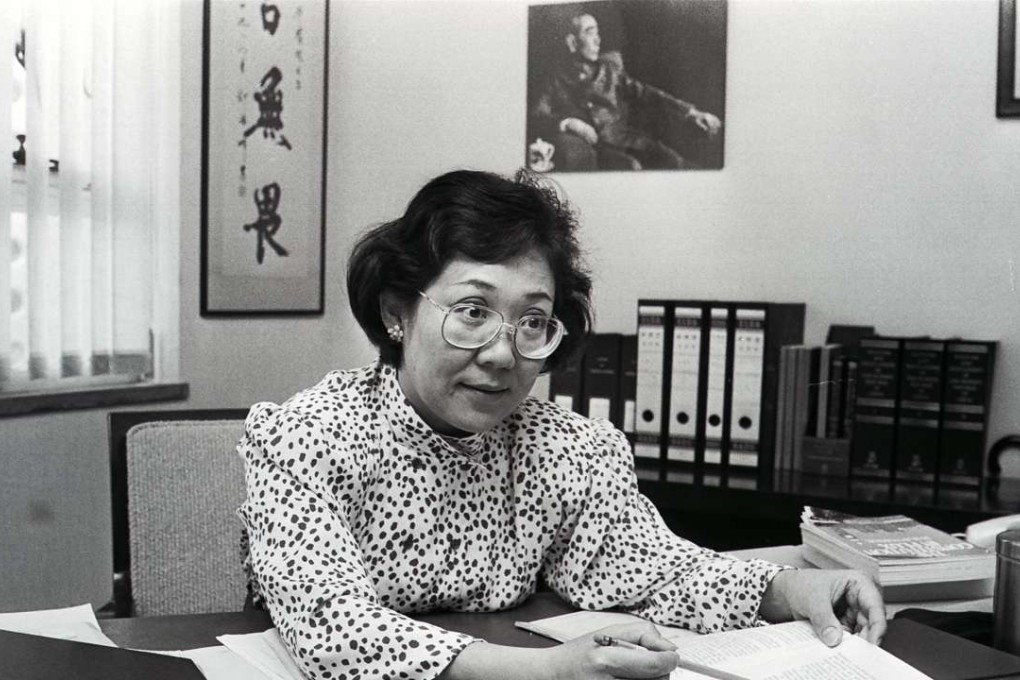

Twenty years ago this month, Dorothy Liu Yiu-chu, lawyer, politician and patriot, died, just weeks before the handover, something that the fiercely anti-colonial Liu had fought for. She brought her legal expertise to bear during the Sino-British negotiations and, later, as a member of the Basic Law Drafting Committee.

Politicians pay tribute as ‘patriot’ Dorothy Liu dies

It is a pity that she died without seeing the results of her handiwork. It is even more regrettable that Hong Kong can no longer benefit from her wisdom. Though she was always described as a “pro-China” politician, the reality was that she was also pro-justice, and very much pro-Hong Kong.

During the squabbles between Britain and China in the 1980s and early 1990s, she was solidly on China’s side. But, after the issue of sovereignty was settled, the debate shifted to the extent of the autonomy that the then British colony could enjoy after the handover. In that discussion, she was firmly on Hong Kong’s side.

After the Tiananmen Square crackdown of 1989, Liu insisted, while delivering a speech in Beijing, on observing a minute of silence in tribute to those who had fallen

This was disconcerting to Beijing, which discovered that someone who was considered a loyalist became one of its severest critics. One example: after the Tiananmen Square crackdown of 1989, Liu, as a Hong Kong member of the National People’s Congress, insisted, while delivering a speech in Beijing, on observing a minute of silence in tribute to those who had fallen. She became known as a loose cannon, when actually she continued to act and speak according to her principles.

She repeatedly stressed the importance of the Communist Party tying its own hands when dealing with Hong Kong, saying that it was so accustomed to exercising total control that merely promising not to interfere in domestic Hong Kong matters was not enough. The party’s nature was to interfere and to control.

She often likened this to a left-handed person promising to use only his right hand. The pledge may well be sincere, but even without the person himself knowing, he will start using his left hand. The only way to prevent this from happening, she said, was to bind his left hand so he could not use it. Thus, the Communist Party had to restrain itself. Otherwise, subconsciously, it would go against its promises of non-interference.

Liu’s voice is sorely missed today. Her family’s links to party leaders, including to the family of Liao Chengzhi, the party’s specialist on Hong Kong matters, would have stood her in good stead. As a long-time friend of the party, she would have unmatched credibility in Beijing.