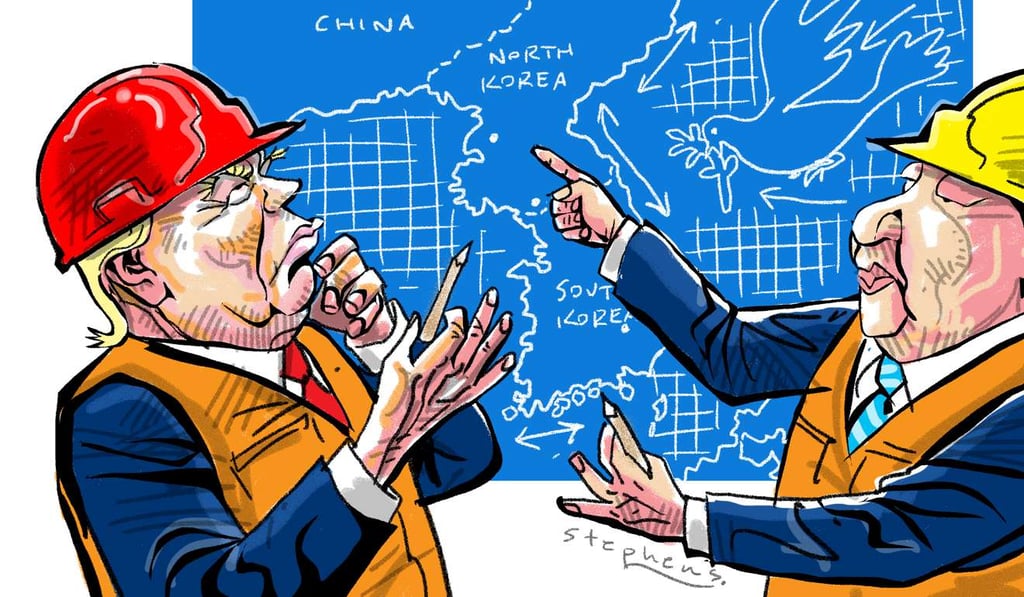

The US needs China’s help to engineer peace on the Korean peninsula

Charles K. Armstrong and John Barry Kotch say Trump must respond to North Korea’s latest missile test not with belligerence but with a resolve to use diplomacy to restructure the Korean peninsula’s security framework

Watch: North Korea hails its new missile test as a success

As a new US administration settles into office, the fourth to confront the North Korean nuclear dilemma since the 1990s (preceded by Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama), a sense of déjà vu is mixed with the realisation that the North is on the cusp of achieving the necessary range and warhead miniaturisation that could put the US homeland in the crosshairs and the US president in a Catch-22. And, given the virtual unanimity among experts that Pyongyang will have such a capability by 2020 at the latest, the Trump administration doesn’t have the luxury of kicking the can down the road.

Unpalatable as it is, Trump should talk to North Korea

How should the US respond to the reality of a North Korean intercontinental ballistic missile capable of hitting the US homeland? One possibility is pre-emption, which risks collateral damage to South Korea (Seoul is already in range of North Korea’s conventional artillery) and Japan. Or reliance on an antiballistic missile system, such as the THAAD defensive shield set to be deployed in South Korea by the end of the year. THAAD, unfortunately, is not foolproof and is seen by China as a threat to its own strategic deterrent capability. Or the US can explore a third way: a diplomatic initiative in concert with China.

For now, however, the Trump administration is most likely to double down on sanctions while accelerating the deployment of THAAD. North Korea is already probably the most heavily sanctioned country in the world and this move would do nothing to alter the reality of Pyongyang’s move towards nuclear capability. Further, most of its trade passes through China, facilitated by Chinese companies, banks and individuals. Beijing is not about to impose punishing sanctions on its Korean neighbour, destabilising a regime that serves as a buffer against encroachment by its southern rival and power projection to China’s border by the United States.

Heat is on China after North Korean missile test