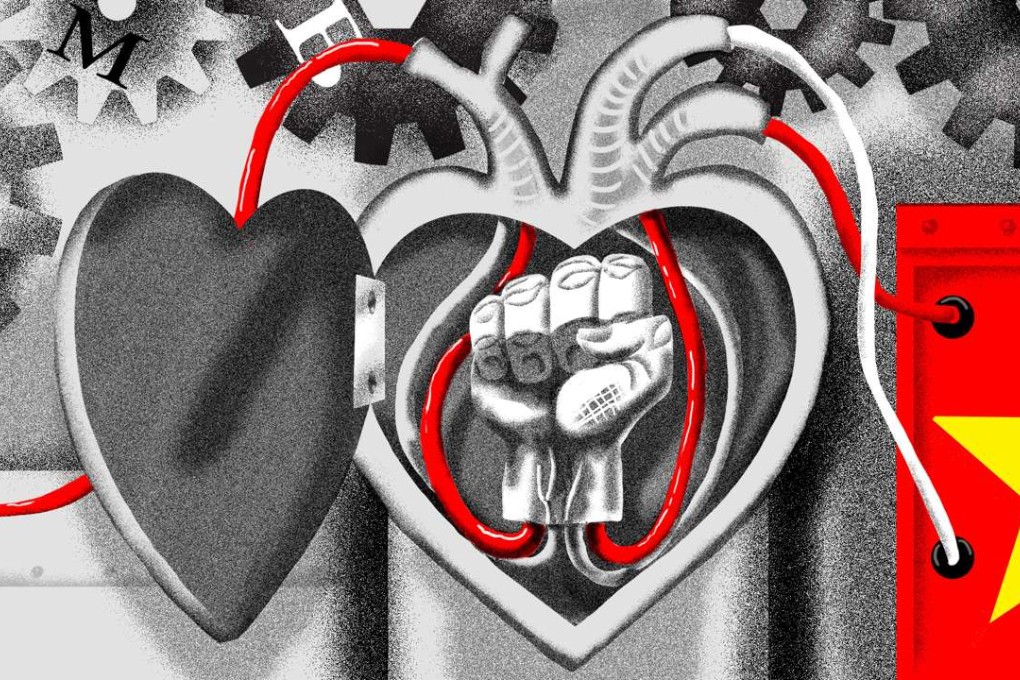

For Beijing, the tycoon class can never rise above the party

Niv Horesh and Kean Fan Lim consider the Chinese government’s challenge of navigating the tension between its authoritarian heart and the private-sector capitalism needed for the country’s growth

China is already the world’s second-largest economy. Though it is slowing, GDP growth over the past three decades has outpaced that of South Korea, Japan or Taiwan at their prime. In fact, some analysts believe per capita income in China today, relative to developed-world levels, is equal to where South Korea was, economically, relative to the US in the mid-1990s. So the figures speak for themselves – but repeated stimulus packages also mean corporations and local governments in China have become heavily indebted well before their country can hop above the middle-income trap.

How politics will decide whether China becomes a high-income economy

Paradoxically, globalisation has enhanced the Communist Party’s governance capacities at home. The party leadership insists communism is still relevant, but has, since the enshrinement of the “Three Represents”, celebrated private enterprise. In fact, there are reportedly more billionaires in the National People’s Congress than there are on Capitol Hill. So much so that America’s most flamboyant entrepreneur, presidential hopeful Donald Trump, has not once pointed to Beijing as a deregulators’ heaven.

Leftists die hard, but Xi Jinping’s blessing for China’s private sector has positive message for economy

Pop-culture heroes in China nowadays are less likely to be loyal party cadres in remote provinces or army generals. Alibaba founder Jack Ma, athlete-turned-businessman Li Ning ( 李寧 ) and self-made automotive tycoon Wei Jianjun (魏 建军) are arguably the new role models. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly harder for China to navigate the contradictions between authoritarianism and freewheeling capitalism.

While some facets of the Chinese economic miracle might bear similarity to high-income Japan, South Korea, Taiwan or Singapore – in terms of the government’s guidance of the private sector or in incipient basic welfare provision – none of these countries comes close to China historically when it comes to the latter’s huge state-owned enterprises.

Will the Chinese variant of the so-called East Asian developmental state model therefore chart a different path to high-income prosperity? And if so, what would the balance between individual freedoms, welfare, employability and free markets be therein?