More sanctions won’t end the Korean nuclear crisis, but engaging Pyongyang in talks might

Charles K. Armstrong and John Barry Kotch call for a high-level US presidential envoy to reach out to North Korea, and convince its leader that dialogue is its best option to break the deadlock

READ MORE: North Korea fires missiles and liquidates Seoul’s assets in response to ongoing war games

Finally, and most importantly, additional sanctions will do nothing to halt, much less reverse, the progress made to date on the North’s nuclear deterrent

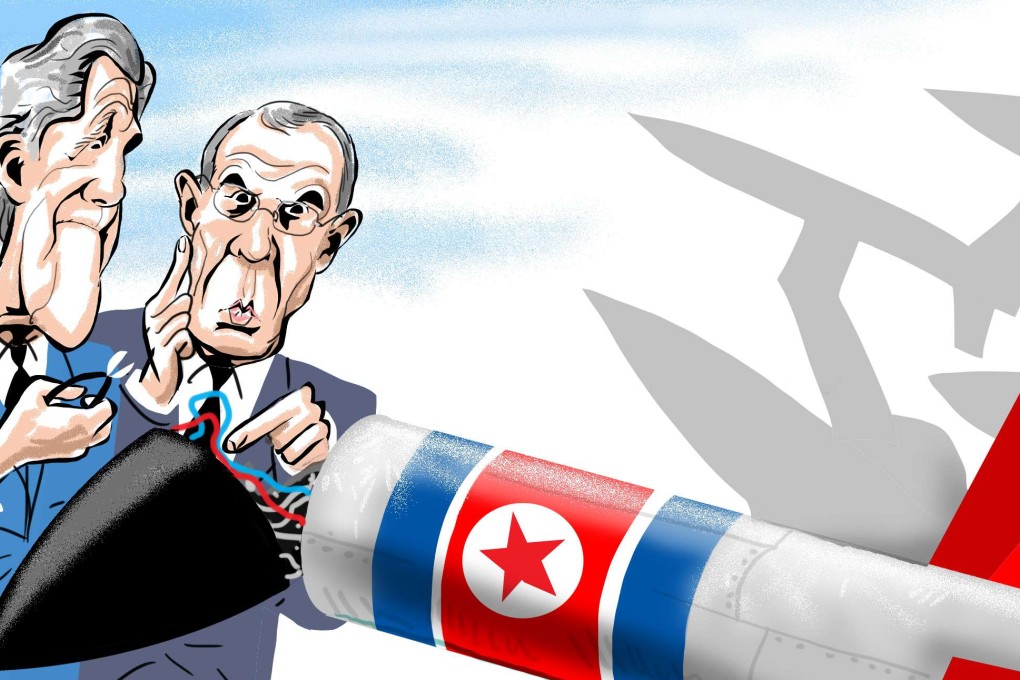

Nor will China agree to a scorched earth economic policy, cutting off necessities like fuel and other imports, given the potential to destabilise the regime.

In short, China fears instability on its borders more than it fears North Korean nuclear weapons. More broadly, the proposed deployment of the Thaad antiballistic-missile defence system in South Korea highlights the region’s geopolitical disarray. Understandably, Beijing views the deployment of a major US strategic asset on its doorstep as threatening, and it is engaging in a war of words with Seoul over the potential of lasting damage to their relationship.

Finally, and most importantly, additional sanctions will do nothing to halt, much less reverse, the progress made to date on the North’s nuclear deterrent.

READ MORE: Tough questions, straight answers: China’s top diplomat on the South China Sea, North Korea, Japan, the US and more

Nor have the prospects improved for US-North Korea negotiations to resume any time soon, given Washington’s refusal to acknowledge the North as a nuclear power state, matched by Pyongyang’s refusal to discuss its nuclear programme as a precondition. Not since the 1994 nuclear crisis, resolved by the timely intermediation of former US president Jimmy Carter, have the two sides been so far apart on fundamentals. In effect, Pyongyang lacks sufficient incentive to take its nascent nuclear deterrent offline, eventually mothballing it permanently, without parallel negotiations to reconfigure the peninsula’s security architecture, the completion of a long overdue peace treaty formally ending the Korean war, as well as the eventual establishment of diplomatic relations.

READ MORE: China’s foreign minister holds talks with US secretary of state on North Korea