Three perspectives to stop the Sino-US strategic drift

David Lampton says despite some positive developments, relations between China and the US are deteriorating as mutual suspicion deepens, and ways must be found to better manage this important relationship

READ MORE: The beauty of restraint in the South China Sea

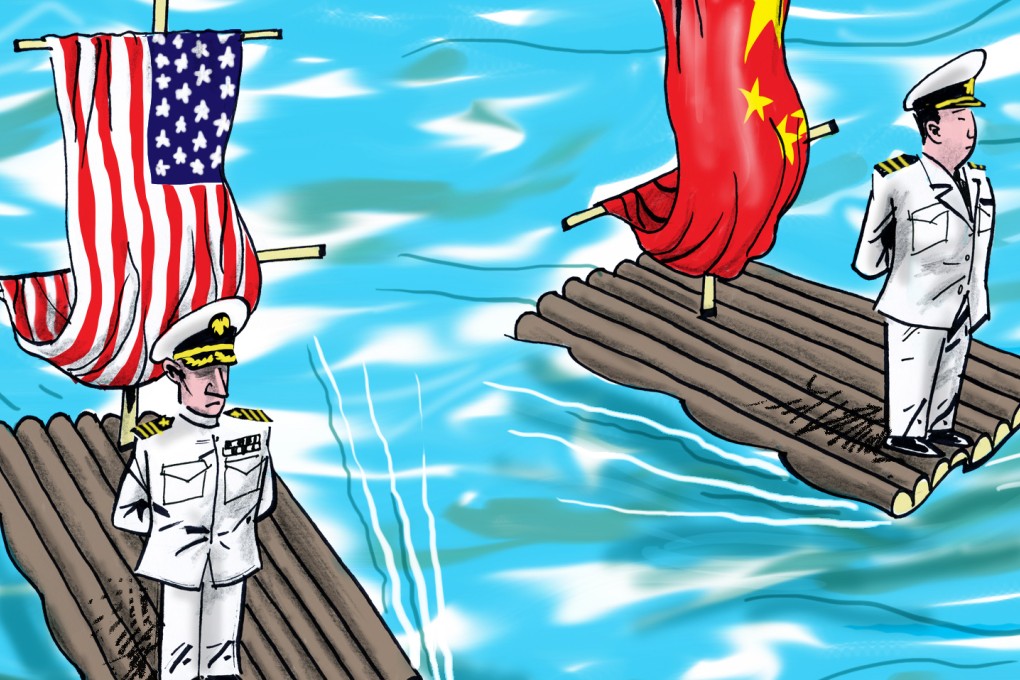

These are troubled times requiring both realistic thought and an empathetic spirit. What attitudes and perspectives should both America and China bring to productively manage our relationship? Of course, translating general guidelines into concrete actions is not easy. But, if public and private leaders in both countries fail to manage the Sino-American relationship well, history will be unforgiving in its judgments. Americans and Chinese must jointly navigate the treacherous waters of a world that has become a very different place from the post-second-world-war era in which the word “superpower” was a relevant concept. The word “superpower” misdirects us in a world of broad interdependence and diffusing power.

The word ‘superpower’ misdirects us in a world of broad interdependence and diffusing power

Also encouraging is mounting Chinese investment in the US, creating 80,000 American jobs in China-affiliated enterprises, and the literally hundreds of thousands of Chinese students contributing to American education and research. Not to be overlooked are current cooperative plans to greatly increase the number of American students learning the Chinese language.

Strategically important is some cooperation with respect to the Iranian nuclear negotiations, anti-piracy initiatives, and joint efforts to combat Ebola in Africa. In short, there are things to celebrate.

READ MORE: From cybersecurity to South China Sea territorial disputes: 5 big challenges and outcomes in Sino-US relations

Consider the South China Sea in recent months. America and China solidify outposts in the region, whether through alliance strengthening, land reclamation, long-term access agreements and base enlargement. In terms of big power ties, Beijing and Washington are each drawing closer to third parties, hoping to restrain one another through triangular, balancing efforts – Washington and Tokyo draw closer, as do Beijing and Moscow. Both militaries are developing new weapon systems, in part aimed at each other.

We are in a downward strategic drift that demands our reflection and action. It was security that brought Richard Nixon and Mao Zedong (毛澤東), and Jimmy Carter and Deng, together. We now find security becoming a net negative in the relationship. This creates the obvious danger of militarisation, which brings with it all the attendant risks of miscalculation, escalation and pre-emption. Continued deterioration will infect the bilateral, economic, cultural, and diplomatic facets of the relationship.

So, what should we do to stop this slide? Three perspectives may offer guidance on managing this relationship.