How middle power Indonesia fits into a changing Asian order

Derwin Pereira says Jakarta's calm acceptance of Japan's new military policy reveals a desire to keep its options open when it comes to regional rivalries, not least Sino-US relations

The recent passage of Japan's security bills marked a watershed moment in Asian strategic relations. For the first time since the end of the second world war, Japan will now be able to dispatch troops abroad. This development has not caused visible disquiet in Jakarta. This is surprising given that Indonesia is part of a Southeast Asian region that suffered from the pathological depredations of Japanese imperial power. However, Jakarta appears to have accepted the potential expansion of Japanese military power as a fait accompli, if not actually as a welcome counterbalance to China's assertiveness in the South and East China seas.

There is another reason for Indonesia's apparent equanimity: America. The US provides the crucial third leg of the Northeast Asian power triangle, acting as a balancer power that helps to preserve the peace between China and Japan as part of a larger effort to uphold security and stability in Asia. Indonesia's acquiescence in Japan's revisionist military posture is a tacit acknowledgement that Jakarta expects Washington's balancing and pacifying role to continue. The US will not let a rising Japan threaten the rest of Asia any more than it will allow China to do so. That is the hope in Jakarta.

The view from Jakarta is not naive. No thoughtful Indonesian believes that the current Asian structure is immutable, even in the medium term. The latest proof of change is Japan's strategic normalisation. After all, it is not extraordinary for a sovereign country to have the right to send its troops abroad, although historically minded critics would deem it the remilitarisation of Japan.

This nuanced position gives Indonesia, a middle power, the ability to act as a swing state in Sino-US relations

But even before Tokyo called the bluff on the resilience of the post-cold-war Asian order, it was palpably clear that China had broken with it. Sensing its strategic opportunity at a moment of American overreach and weakness brought about by expensive yet inconclusive wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Beijing pushed ahead to unsettle the Asian maritime status quo. Chinese revisionism has now produced its Japanese counterpart.

However, the fact that the Asian order is changing does not mean it is spinning out of control. What is occurring in Northeast Asia is a relative and not an absolute redistribution of power among China, Japan, South Korea and the US. China is making relative gains from its hitherto peaceful rise, and America is chalking up relative losses imported from its overstretch in West Asia. Washington has responded to its relative decline by initiating a pivot to the Indo-Pacific that is clearly aimed at containing the prospects of Chinese maritime expansionism.

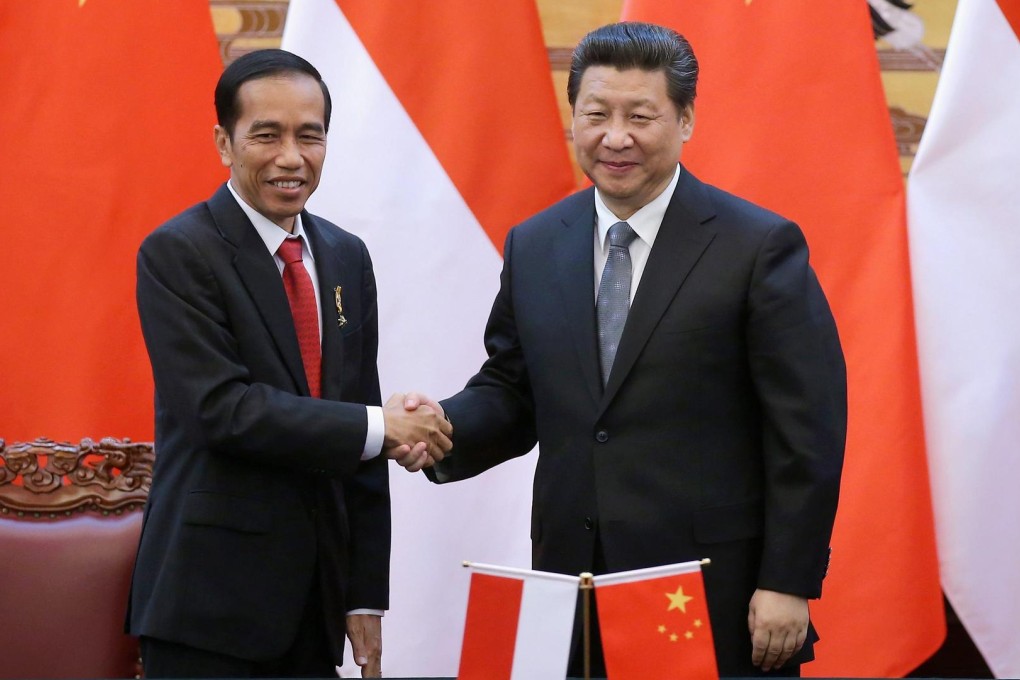

This nuanced position gives Indonesia, a middle power, the ability to act as a swing state in Sino-US relations. What it is likely to seek increasingly is recognition from the US, China, India and other Asian powers of its lynchpin role in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Asean constitutes buffer territory between China and India. The organisation is likely to be split by strategic competition between those two countries, with America and Japan acting as a brake on Chinese ambitions.