Officials impede Hong Kong's progress by blocking freer flow of information

Jane Moir says a law is long overdue to raise the standards of governance and accountability

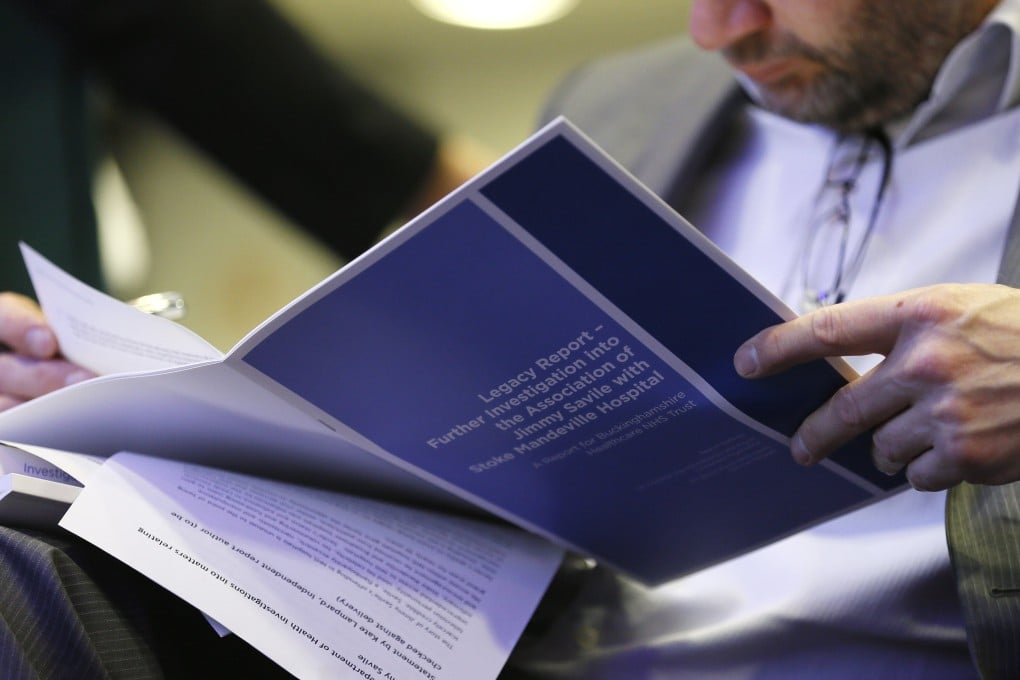

Important stories in the public interest have been crafted from freedom of information requests. In Britain, revelations of parliamentarians' expense claim abuses, the London police's proclivity for tasering children and the trigger for a full inquiry into celebrity paedophile Jimmy Savile's abuses in public hospitals resulted from landmark legislation adopted a decade ago.

In Britain's experience, a freedom of information law has been, on the whole, a positive force for governance and accountability. Though critics have pointed to some unintended consequences, such as internal communication within government being "dumbed down" through fear of future embarrassment, there is no serious proposal to return to the old days of "mother knows best".

The law has shifted the bureaucratic disclosure pendulum from secrecy-at-all-costs to a right to know. And the parameters of this right are put to the test in the courts.

Twenty years ago this month, Hong Kong introduced a voluntary code on access to information. Sadly, the impact has not matched the experience in the UK or even other jurisdictions in the Asia-Pacific region. In fact, the disclosure pendulum is stuck in the mid-1990s and the culture of accountability for public officials may even have regressed.

If Hong Kong wants to be taken seriously as a "world city" with a genuinely accountable bureaucracy, a good start would be to replace its voluntary code with a law. Somewhat absurdly in a city full of quasi-public bodies, the code covers only government departments and just two public organisations. Other public bodies have the option to join, but face no compulsion; just 22 have signed up, even though Hong Kong has 470 advisory and statutory bodies whose operations are funded with public money.

While the right to information is guaranteed under the Bill of Rights, the code itself has no legal backing. Denials of information or partial responses can be taken to the Ombudsman, who can investigate and make recommendations. However, the government watchdog has no power to compel information and cannot impose sanctions for failing to do so.

Departments can easily bat back requests aided by 16 formal exemptions that include the somewhat opaque "management and operation of public service". Denials of information are often inconsistent, misplaced or unwarranted. Most of the stories emanating from access to information requests are scathing indictments of the process itself.