Reforms will stall unless Beijing tackles vested interests

Keyu Jin identifies the two conflicts that are impeding progress

China's reform programme has reached an impasse, with fundamental conflicts of interest and subtle resistance mechanisms blocking progress. Until these barriers are removed, there is little hope that China's slowing economy can rely on reform to give it the push it needs.

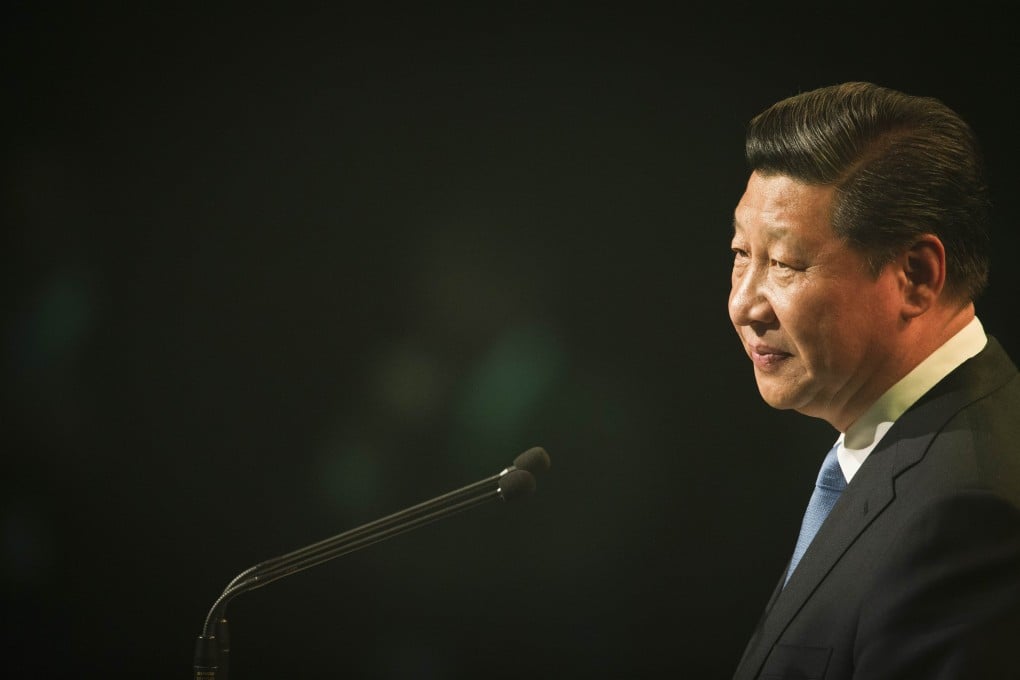

Chinese leaders are well acquainted with how difficult it can be to implement drastic reforms. When Deng Xiaoping launched his "reform and opening up" in 1978, he faced fierce opposition - mostly from fervent ideologues and revolutionary diehards. Just as Deng's status and forcefulness enabled him to face down his opponents, President Xi Jinping's determined leadership can overcome vested interests and implement the needed reforms.

Of course, reconciling the fundamental misalignment of interests in China will not be easy - not least because interest groups will not discuss, much less oppose, reforms openly. Instead, they argue that the reforms are too risky. Only small concessions have been made to scaling back government intervention, affecting powers that are either irrelevant or never actually existed.

There are two types of conflicts of interest among the government bodies. First, China's powerful bureaucracy is disinclined to cede its powers in the name of liberalisation and a shift towards a more market-oriented economy.

For example, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council is the ministry-level government institution responsible for state-owned enterprises. Its task now includes eliminating the state-owned enterprises' monopoly power, which is hampering market competition. But reducing their power would also mean a diminished role for the commission - and, most likely, its eventual obsolescence. As a result, efforts to fight monopoly are lagging, and the next stage of reform - the transition to a "mixed ownership system" - remains distant.

The second major conflict of interest is between the central and local governments, which are supposed to be adjusting their revenue-sharing model. The problem lies in a mismatch between their respective shares of tax revenues and mandatory expenditure. With local governments forced to cover a large proportion of public spending with a disproportionately low share of revenues, local-government debt has swelled.