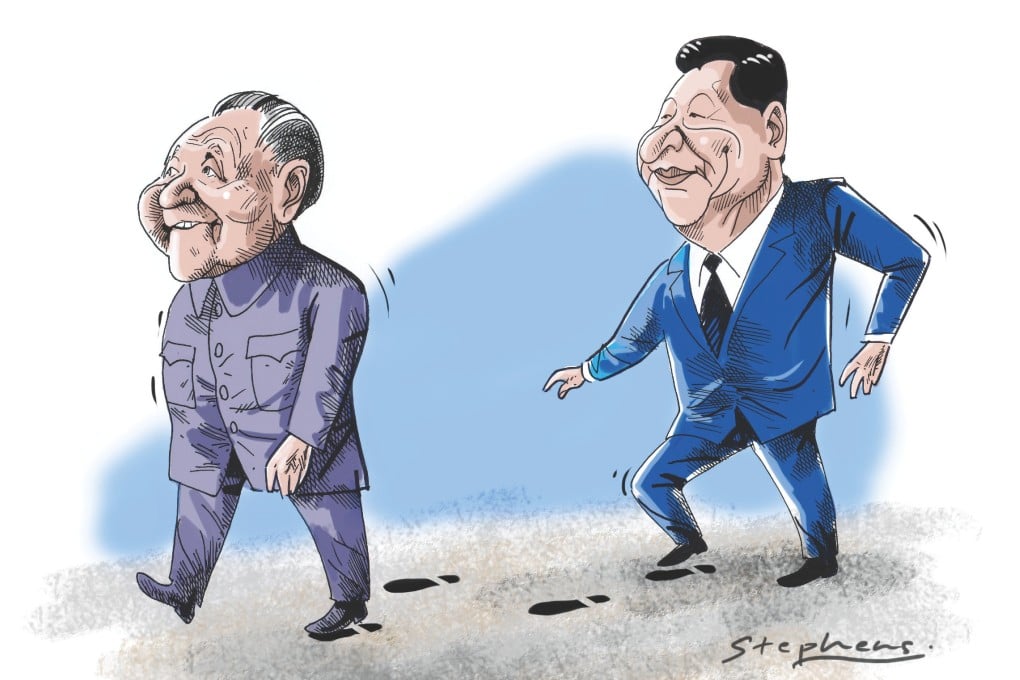

Xi proves to be no Mao follower, but a disciple of Deng

Robert Lawrence Kuhn says the third plenum should lay to rest speculation about whether Xi Jinping is a reformer; he is clearly a pragmatist, as was Deng Xiaoping

For the past year, ever since Xi Jinping was confirmed as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, the big question has been: Is Xi a reformer? Now, after the third plenary session of the 18th Central Committee, we have our answer. It is neither "yes" nor "no".

Without doubt, the third plenum institutes systemic reforms that seek to transform China's economy and society. Specifics will come later and implementation will take years, but major reform is finally policy, not rhetoric. It is Xi's unambiguous commitment that the market must drive the economy, government retreat to regulation and oversight, farmers and migrant workers have equal rights and opportunities, and judicial system reform "deepen".

All and more are paragons of reform. That some reforms were not enacted, particularly breaking the monopolies of state-owned enterprises, should be viewed with the lens of political expediency.

In addition, early in his first year, Xi seemed to articulate a liberal agenda: curbing official extravagances, praising China's rights-protecting (but largely irrelevant) constitution, and suggesting some form of judicial independence. More recently, Xi backed Premier Li Keqiang in establishing the Shanghai free-trade zone.

Intriguingly, Xi called for the party, which maintains atheism as an article of faith and requirement for membership, to be more tolerant of China's "traditional cultures" or religions. Though he did so to halt moral decay and fill the spiritual vacuum created by market-driven materialism, this was no hard-core Marxist at work. (Xi's father, former vice-premier Xi Zhongxun was respected as a far-sighted visionary on ethnic and religious affairs.)

But initial hope and optimism among liberals gave way to growing dismay and pessimism as China tightened media controls, policed social media, detained liberal activists and forbade discussion of "universal values" such as civil society, judicial independence and press freedoms. In internal speeches, Xi used the collapse of the Soviet Union and the overthrow of the Soviet Communist Party as a case study of what the party must never permit. For sure, Xi will not be "China's Gorbachev".