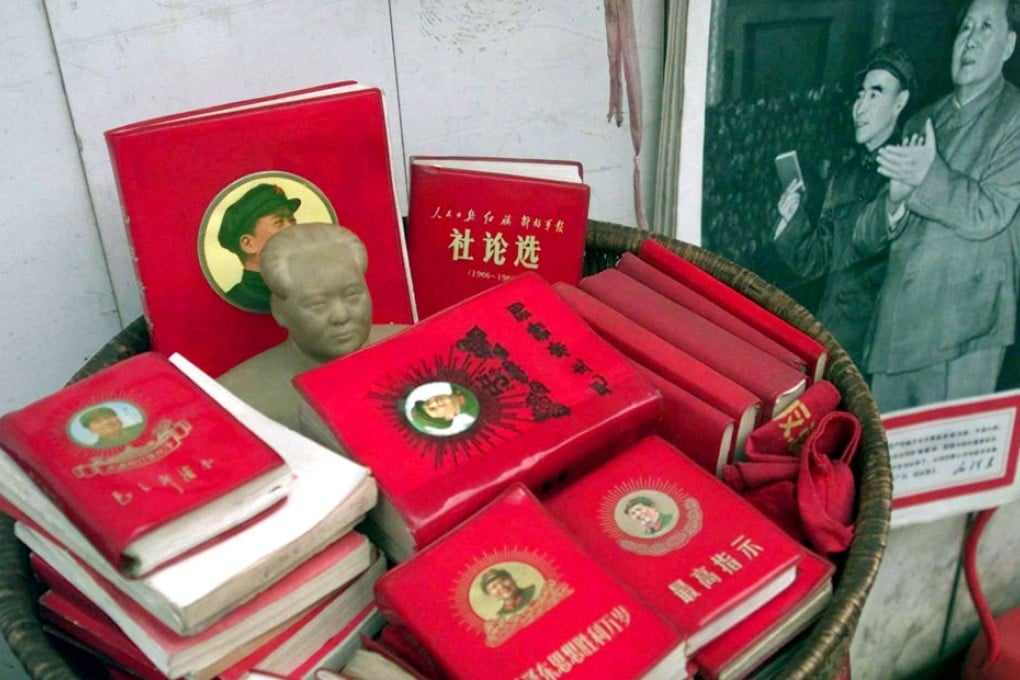

'Little red book' republication saga is all about political control

Chang Ping considers the costs of China's refusal to face up to causes of the Cultural Revolution

To the relief of many people, Xinhua issued a one-line statement on National Day denying reports that a new edition of would be published this year.

But this was no rumour. After all, in the earlier media reports on the republication of the title - better known as that symbol of the Cultural Revolution, the "little red book" - the book's editor Chen Yu, a researcher at the Academy of Military Sciences, was widely quoted on details of the edition.

Since he came to power, Xi Jinping's words and deeds have caused concern that a second Cultural Revolution is on its way: his affirmation of the validity of the 30 years before economic reforms; his push for a mass line campaign; the organised attack on constitutional rule; the crackdown on internet "rumours"; and the lack of any attempt to discredit the Chongqing model during Bo Xilai's trial.

In 1981, under Deng Xiaoping's leadership, the "Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party" adopted at the sixth plenary session of the 11th Central Committee famously denounced the Cultural Revolution and called for reform and opening up. Yet, only two years earlier, Deng had pledged to uphold the "four cardinal principles", which included upholding "the people's democratic dictatorship", and Marxist-Leninist and Maoist thought. These principles clearly contradicted the denunciation of the Cultural Revolution.

In light of this, Xi was only being faithful to Communist Party thinking about the Cultural Revolution: party leaders have never rejected the Cultural Revolution except when it became expedient to do so in a power struggle. If this weren't the case, serious reflection on the turbulence would not have remained a taboo till today, a purported attempt to study Maoist thought would not have stirred such unease, and the longed-for Cultural Revolution museum would already have been built.

In the 1980s, some reflection on the Cultural Revolution was allowed in academia, the arts and the media, albeit within strict limits. Such a review was valuable, to a degree, but because it touched a nerve it was soon banned.

These broad strokes of reflection unfortunately did not address the deep-rooted problems of the 10-year trauma. Today, its very superficiality has led to some confused thinking.