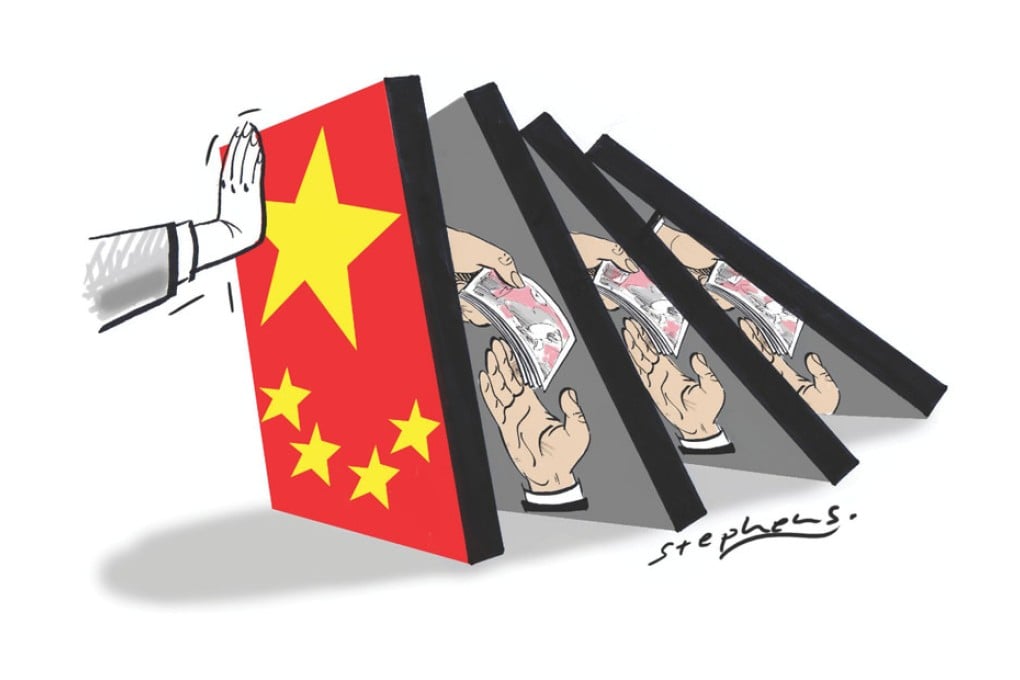

China's crackdown on corruption is Communist Party's 'New Long March'

G. Bin Zhao says China's crackdown on corruption will be a long, hard battle but it must be fought openly and with integrity to avoid social and political turmoil and damage to the economy

These days, the phrase "anti-corruption" is perhaps among the most common to be found in the Chinese media, and it echoes through all levels of public discussion. The GlaxoSmithKline bribery scandal has created panic among some multinational executives in China, particularly within the pharmaceutical industry. A number of government officials at various levels, as well as senior managers of state-owned enterprises, have been greatly concerned too, fearful that they might be next in line as top leaders strive to build a corruption-free government.

The anti-corruption campaign's achievements have garnered muted praise from the public, yet this is just the prologue to a "New Long March" that the Communist Party will have to endure.

The original Long March, which started in 1934, was without doubt the bitterest struggle the party has ever faced but, fortunately, it enabled it to recover from the brink of failure.

In the eyes of many, the ongoing war against corruption is also a life-and-death matter, not only for the party, but also for the country as we know it. But it is worth noting that there is concern, both domestically and internationally, that the anti-corruption campaign might create another uneven playing field in China's business and political environments.

As an example, GlaxoSmithKline has admitted that its executives did indeed bribe some doctors and health care officials in order to boost its sales in China. Nobody would argue about the legality of such behaviour; it definitely violates Chinese law. Bribery is top of the list as a means of facilitating corrupt activities worldwide, and it cannot be tolerated in any country.

However, as one informed analyst, with the backing of many others, has said: "In reality, who does not bribe the doctors and officials in the Chinese pharmaceutical industry? It is a very common practice and many companies are doing it. Compared to the multinationals, local enterprises are even worse because they have poor products and barely conduct any research and development on new drugs."

So, it seems that GSK's behaviour is not an isolated case but, sadly, an industry practice which has existed for years. So, why has it been singled out for investigation? Why has it become the "lamb to the slaughter" in the current anti-corruption campaign? And why has this case received especially intensive coverage from CCTV, the most influential and popular state-owned broadcaster, boasting more than one billion viewers? Such coverage is rare in the extreme.