For Taiwanese, the mainland remains a dangerous place

Jerome A. Cohen and Yu-Jie Chen say legal safeguards remain inadequate for Taiwanese suspected of a crime on the mainland despite hopes of reform to allow greater security for detainees

Going to the Chinese mainland can be dangerous. First-time visitors are often surprised at their freedom, and seasoned travellers may feel comfortable, but foreigners do get detained by police for many reasons. When commercial dealings sour, businesspeople of Chinese descent, including those from Taiwan and Hong Kong, are especially at risk.

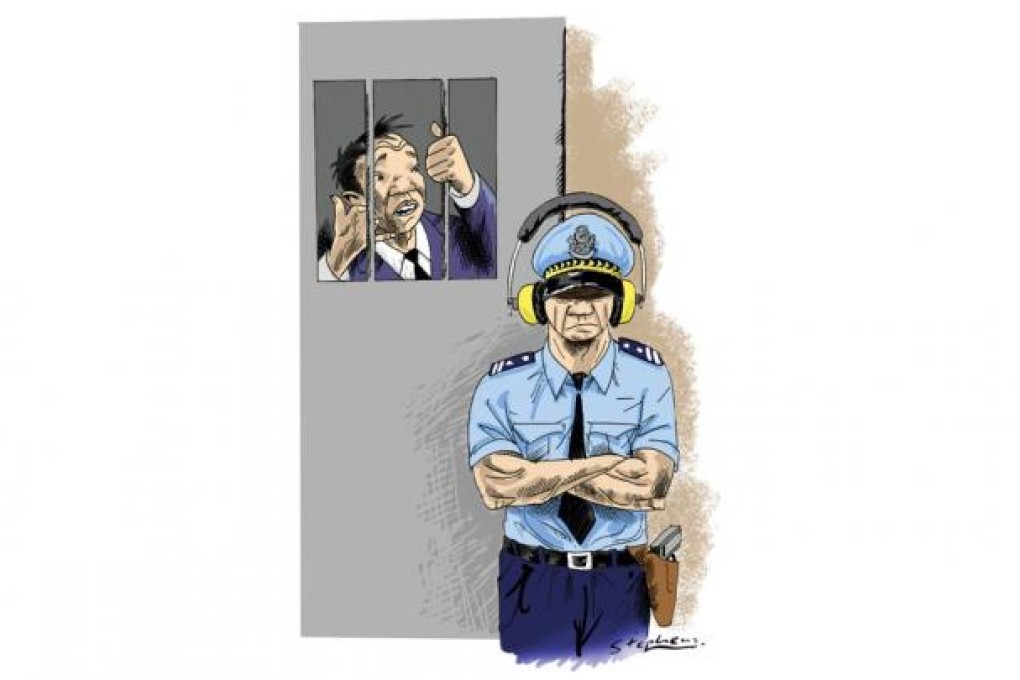

To be sure, China has enacted laws to better protect the rights of criminal suspects. On January 1, a newly amended Criminal Procedure Law will go into effect, with many provisions aimed at remedying police abuses. Yet, despite reformers' best efforts, the law has many ambiguities and exceptions. Moreover, rather than fill in the gaps in good faith, in practice law- enforcement officials frequently twist even clear legal language and sometimes act totally outside the law. The system provides no effective way to challenge such government lawlessness.

Every detained foreigner confronts the same problems as detained Chinese. When will someone tell my family or colleagues where I am and why? Can I meet them? Can I meet a lawyer? Who can help me regain my freedom? Most nations rely on international agreements to protect their citizens from arbitrary detention abroad. The Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, to which China adheres, requires detaining governments not only to inform the detained person of his right to have his consulate notified, but also to allow consular officers to visit and arrange legal representation. Many nations have bilateral consular agreements with China that specify more detailed protection.

Although imperfect, these international guarantees give foreign nationals greater security than that enjoyed by Taiwanese on the mainland. The Republic of China government's acceptance of the Vienna convention is no longer recognised, and it has neither a consular agreement nor even formal diplomatic contacts with the People's Republic. Yet millions of Taiwanese visit the mainland, and hundreds of thousands live and work there.

In 2009, Taiwan sought to resolve problems of detained citizens with the Agreement on Joint Cross-Strait Crime-Fighting and Mutual Judicial Assistance. Yet that document merely required each party to "promptly" inform the other of any relevant detention. No specific time limit was stipulated, and the authorities were given discretion to postpone notification if it would "hinder ongoing investigation, prosecution or trial procedures". Moreover, Beijing's subsequent disappointing implementation of this safeguard did little to ease the anxieties of Taiwanese visitors.

Many in Taiwan anticipated that the Cross-Strait Bilateral Investment Protection and Promotion Agreement, which was signed on August 9 and reflected considerable progress in establishing methods of resolving cross-strait commercial disputes, would finally guarantee notification of detention in every case, at least for Taiwanese investors and their families. They hoped that the agreement would also prescribe what information must be given, and the rights of the detainee, his family and their lawyers. To their surprise, neither it nor its appendix includes such provisions. Instead, the parties issued a separate "statement of common understanding" that gives the appearance of increased security without the substance.

This unusual statement provides that, after taking criminal justice "compulsory measures" against Taiwanese investors, their Taiwanese employees or accompanying family members, mainland public security authorities must inform a detained person's family on the mainland within 24 hours. If the detainee's family is not on the mainland, the statement merely indicates that the police "may" inform the investor's company.