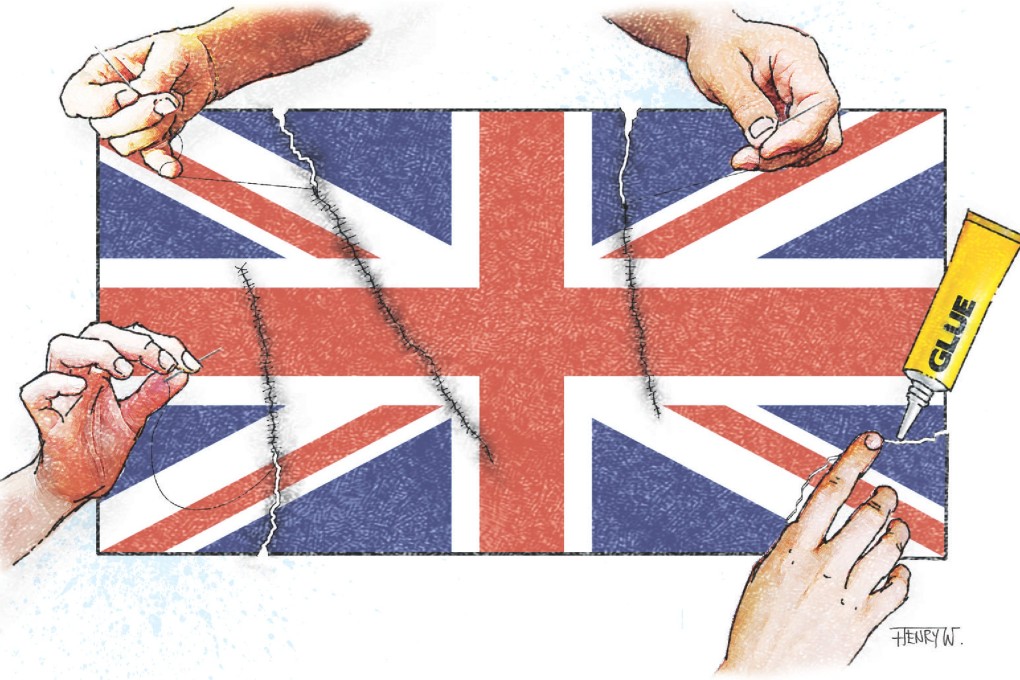

Now the UK must heal itself

Chris Patten says despite the inherent flaws in referendums as a way to decide political issues, democracy won out in the Scottish independence vote, and it's now time to restore reason and repair divisions

In the end, democracy came to the rescue. The people of Scotland voted by a comfortable margin of about 10 per cent to remain part of the United Kingdom - not least because of the campaigning of three Labour politicians, Alastair Darling, Gordon Brown and Jim Murphy.

At times, it seemed that the result would be much closer, or even that we British might engineer the dismemberment of our country, which for centuries has brought together four national communities: England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland. The Scots have been part of the British state for more than 300 years, at the heart of the Protestant, imperial, adventuring, outward-looking culture that forged Britain's identity. Still, that identity has been fractured; I hope not beyond repair. In any case, things will never be quite the same again.

Now, the people of England, Wales and Northern Ireland - not rejected, after all - must behave as well as possible to salvage something workable from the sometimes bitter and divisive arguments. We have to display magnanimity - a difficult enough virtue to practise at the best of times. Before trying to rise to this challenge, what can we learn from this walk along the cliff edge?

Despite the huge turnout on polling day in Scotland, referendums are a lamentable way of trying to settle big political issues. Those who established and developed parliamentary democracy in Britain knew this very well. Referendums are the favourite device of populists and would-be dictators. One vote on one day subsumes complex matters with one ballot question, which in any event is frequently not the question that many people actually answer. Parliamentary democracies should have nothing to do with them.

In the event, we did not dispose of 300 years of shared experience and common prosperity on one Thursday in September 2014. But there are three reasons why we seemed to come so close to that outcome, none of which reflect well on the British political process or justify the claim that our future will, and must, be different.

First, while Scottish nationalism has many honourable roots and aspirations, the campaign and its incubation showed a nasty tinge of chauvinism and an occasionally brutish hostility towards pluralism, reflected, for example, in the intimidation of some journalists. Overall, the English took on the role of what philosophers and social scientists call the "other", an alien threatening force, in the pro-independence campaign. The English were every day's villains. Now we have to try to forget all of that.

Second, Britain, like other countries in Europe, is suffering from the rise of angry, populist, anti-enlightenment political forces, fuelled by conspiracy theories. In England, the electoral success of the UK Independence Party is one such example. Demagogues stack prejudices atop half-truths, and any attempt to connect discussion with reality is shot through with accusations of dishonesty and self-interest. Responsible political leaders will have to be more aggressive, bold and vigorous in confronting such interlocutors.