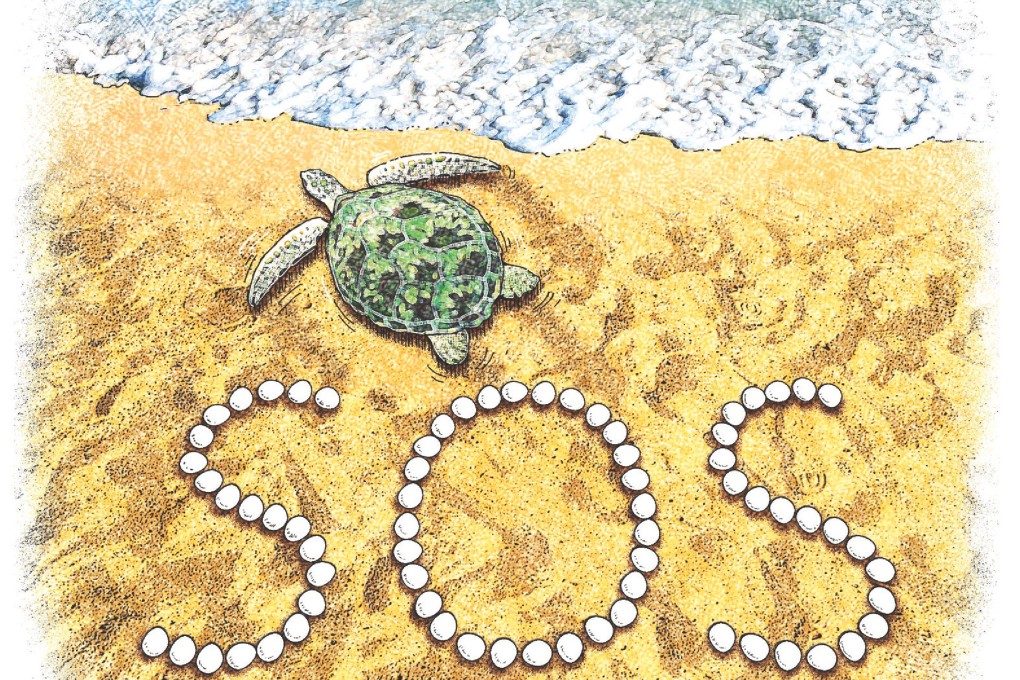

Give Hong Kong's green turtles a fighting chance to survive

Michael Lau says if Hong Kong wants to safeguard its endangered green turtle population, action is needed to protect the waters around the last remaining breeding ground on Lamma

Seven species of sea turtle inhabit the world's tropical and subtropical waters. Six of these are threatened, while the status of the Australian flatback turtle is listed as "data deficient". Sea turtles face a multitude of threats, from being accidentally caught and drowned in fishing nets to the overexploitation of their eggs at their nesting beaches.

Five species of sea turtle can be found in Hong Kong. One of them, the green turtle, actually nests here. This giant used to nest on the beaches of several offshore islands, and the eggs were harvested and sold by local villagers. Now, only Sham Wan on Lamma Island supports a very small breeding population.

A decline in sea turtle populations has been observed in many locations across Asia. One increasingly significant cause is the exploitation of turtles for trade in their products or even in whole specimens.

A report by Traffic, the wildlife trade monitoring network, indicates that there has been an increase in demand for sea turtle products in China. There have also been strong indications that some fishing vessels from China are targeting sea turtles in their operations in tropical Asia. This is reflected by a growing number of cases of Chinese fishing vessels being detained by Southeast Asian countries and protected sea turtles being found on board.

Green turtles are slow to mature: it takes between 26 and 40 years before they are able to breed. Once they reach adulthood, they have few natural enemies and can live and reproduce for a long time.

The most vulnerable stages of their lives come when they are in the egg and when they are small hatchlings. It is estimated that only two to three turtles in every thousand survive to return to their natal beaches to breed.

Their exceptional orientation abilities ensure that they can find their way across vast oceans to return to the natal beach to nest; however, when subject to heavy exploitation, breeding becomes extremely difficult and it takes a long time for a depleted population to bounce back, as there is unlikely to be any "recruitment" from other, healthier populations.