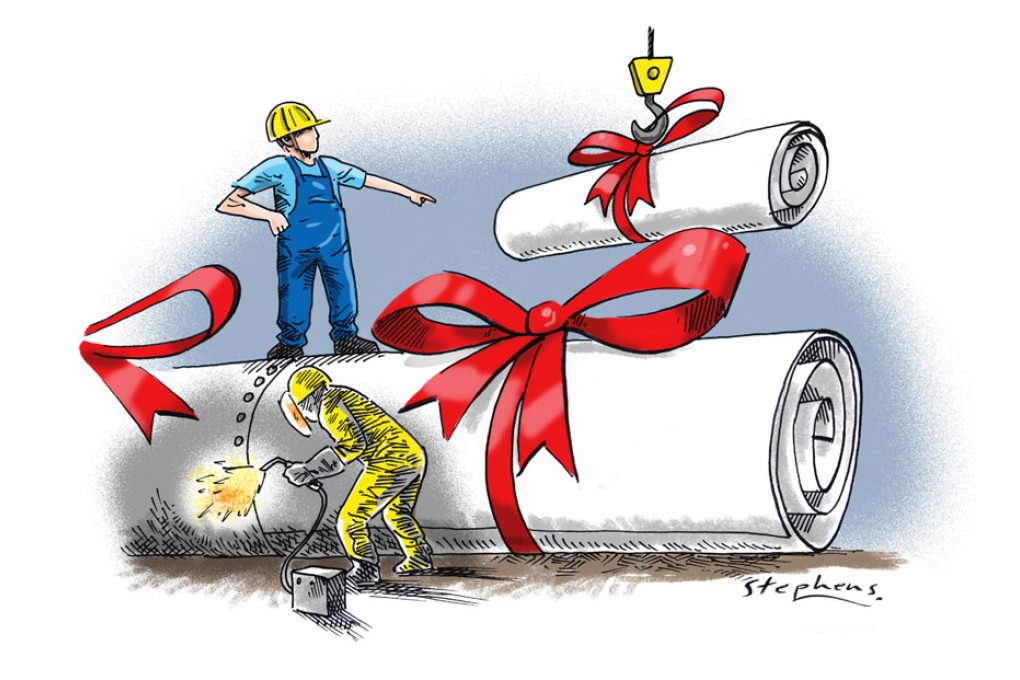

China cannot overcome its growth challenge without the right talent

Lee Jong-Wha says China's growth trajectory and demographic shifts will scuttle its ambition to become a high-income economy unless it revamps its education system and creates a better skilled workforce

Over the past 35 years, China's strong and sustained output growth - averaging more than 9.5 per cent annually - has driven the miraculous transformation of a rural, command economy into a global economic superpower. In fact, according to the World Bank's most recent calculation of the purchasing power of aggregate income, China is about to overtake the United States as the world's largest economy. But, in terms of the quality and sustainability of its growth model, China still has a long way to go.

Despite its remarkable rise, China's per capita income, at US$10,057 (adjusted for purchasing power) in 2011, ranks 99th in the world - roughly one-fifth of US per capita income of US$49,782. And reaching high-income status is no easy feat. Indeed, many countries have tried and failed, leaving them in a so-called middle-income trap, in which per capita income levels stagnate before crossing the high-income threshold.

Strong human capital is critical to enable China to escape this fate. But China's labour force currently lacks the skills needed to support hi-tech, high- value industries. Changing this will require comprehensive education reform that expands and improves opportunities for children, while strengthening skills training for adults.

To be sure, over the past four decades, the quality of China's labour force has improved substantially, which is reflected in impressive gains in educational attainment. Gross enrolment rates at the primary level have surpassed 100 per cent (with the inclusion of overage and underage students) since the 1990s, while secondary and tertiary enrolment rates reached 87 per cent and 24 per cent respectively in 2011. In 2010, more than 70 per cent of Chinese citizens aged 15-64 had received secondary education, compared to about 20 per cent in 1970.

Furthermore, Chinese students perform well in internationally comparable tests. Fifteen-year-olds in Shanghai outperformed students from 65 countries and regions, including the advanced economies, in maths, science and reading, according to the Programme for International Student Assessment in 2009 and 2012.

China has also benefited from rapid employment growth, with more than seven million people entering the workforce each year since 1990. This, together with the massive reallocation of workers from rural to urban areas, has supported the labour-intensive manufacturing industries that have fuelled China's economic rise. But China's demographic advantage is diminishing, owing to low fertility rates and population ageing. According to the UN, by 2030, China's working-age population (15-59 years old) will have fallen by 67 million from its 2010 level.