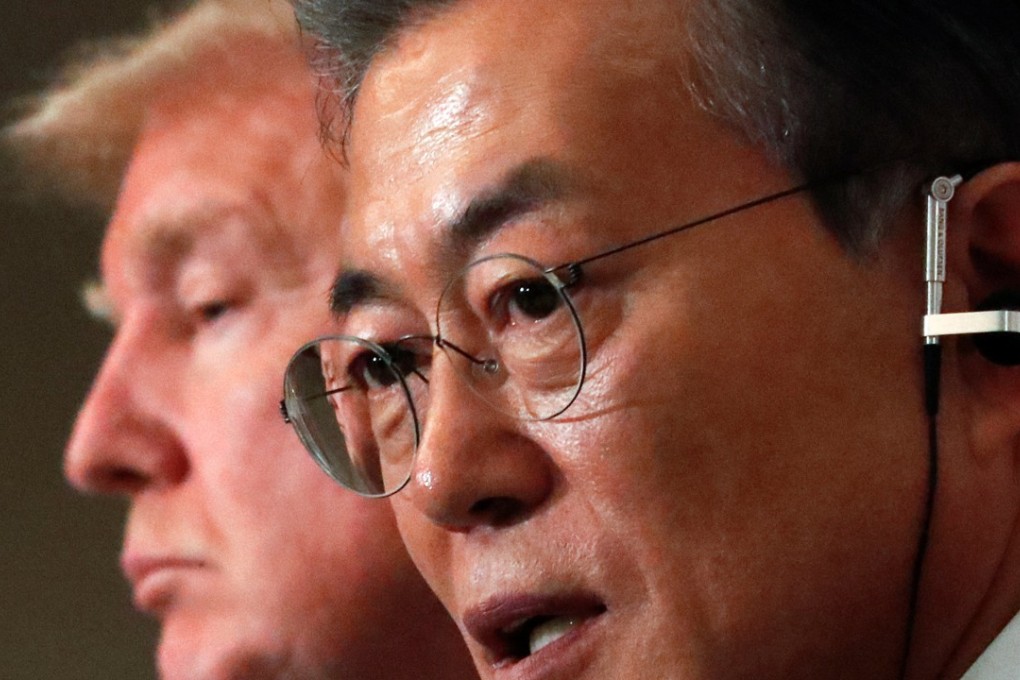

Opinion | With an ally like Trump, does South Korea’s president Moon Jae-in really need an adversary?

South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in did not blame Donald Trump for last week’s epic cabinet shake-up. But the US president’s name was written between the lines in bold type.

President Moon axed five of his ministers overseeing everything from trade to labour to defence. Moon, 480 days in office, faces growing discontent over a slowing economy, an intensifying trade war and setbacks on North Korea disarmament. But his desperate ploy for stability speaks volumes about Asia’s precarious position in the Trump era.

Moon’s plight rests partly with a terrible decision. In May 2017, he was elected to shake up a corrupt and inefficient corporate sector. Instead, he pivoted to North Korean peace. A very important pursuit, of course. But one going off the rails, thanks partly to Trump’s buffoonish behaviour.

Now, so are Moon’s pledges to retool a South Korean economy in harm’s way from Trump’s tariff arms race. Moon won the 2017 election promising to wrestle power away from the handful of family-owned conglomerates towering over the economy. He promised to catalyse a start-up boom, support small-to-medium enterprises and encourage greater risk taking.

So did his predecessor Park Geun-hye, of course. When she assumed the South Korean presidency in 2013, Park promised to reduce the dominance of family-owned conglomerates, known as “chaebol.” She wanted to increase support for small-to-mid-sized enterprises, step up antitrust enforcement and build a more “creative” economy.

Instead, she got co-opted by a system created by her father Park Chung-hee. In 2017, Park Geun-hye was removed from office on bribery and influence peddling charges. The controversy also tripped up Samsung’s de facto leader Lee Jae-yong.

But South Korea’s open economy is flashing warning signs for the rest of Asia. On Friday, the Bank of Korea left interest rates alone, while officials doused expectations for additional tightening moves this year. It’s quite an about-face, given that the BOK in late November became the first major Asian monetary authority to tighten monetary policy since 2011.