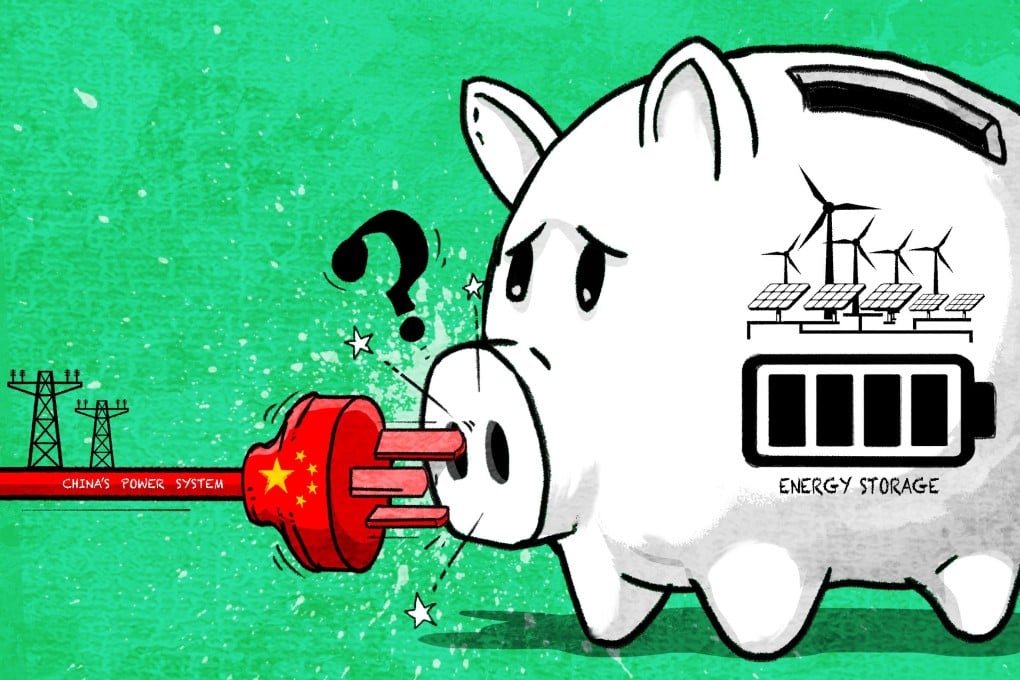

Is China’s trillion-yuan emerging energy-storage market already in turmoil?

Massive spending leads to new equipment sitting underused – or idle – even as the grid sorely needs it to make the best use of clean energy

In China’s eastern Shandong province, massive underground caverns in ancient salt deposits will soon play a role in securing the country’s decarbonised future by storing the energy generated by solar and wind power facilities.

State-owned conglomerate China Energy Construction Corp (CEEC) is pouring more than 20 billion yuan (US$2.8 billion) into the project, which when completed will be the world’s largest facility of its type. It will use electricity to compress air inside the caverns, then use that compressed air to turn turbines to generate electricity again when it is needed.

With a capacity of 3,060 megawatts, the plant will be able to release 4 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity per year, enough to power more than 600,000 households, CEEC said when it announced the project in July.

The ambitious plan is just one example of a boom in energy storage in China. The electrical grid needs such storage to make better use of the country’s world-leading renewable energy infrastructure and boost energy security. As a result, companies and local governments are rushing into what they see as the next trillion-yuan opportunity driven by China’s clean-energy transition. However, the market is already beset with overcapacity and low usage rates, problems that are being exacerbated by government policies and shortcomings in the power system.

“There is a mismatch between the current development of energy-storage systems and what China’s power system really needs,” said Guo Shiyu, a Beijing-based campaigner at environmental group Greenpeace.

A booming market

In addition to being the largest of its type, the Shandong salt-cavern project will also be the world’s largest grid-storage project that is not based on pumped hydro – a traditional method of storing energy by pumping water into an elevated reservoir, then letting it run back downhill to drive turbines when power is needed.