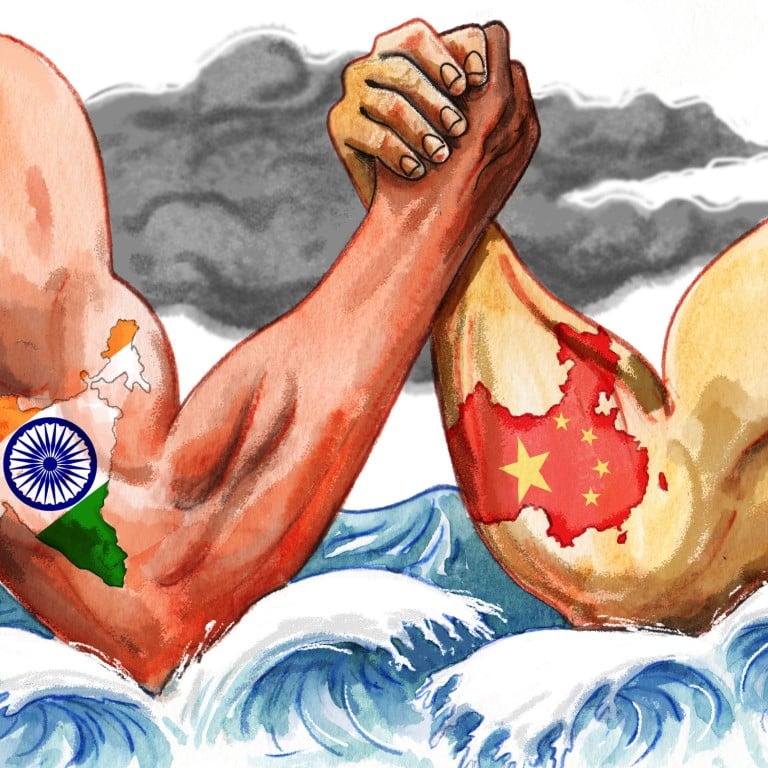

China-India row over Yuan Wang 5 ‘spy ship’ is sending ripples through the Indian Ocean

- The docking of the Chinese vessel in Sri Lanka put India on its guard amid tense bilateral relations

- Both nations depend on maritime security for economic growth, making the Indian Ocean a key arena for geopolitical contests of power

At the time, Indian support to Sri Lanka in the form of emergency food, fuel and financial packages was critical; it thus appeared that Colombo was deferring to Indian sensitivities over a Chinese “spy ship” in a port proximate to peninsular India.

In a pithy and sardonic summary of the entire sequence of events, Ambassador Qi Zhenhong, the Chinese envoy to Sri Lanka who was in Hambantota to receive the vessel, said when asked about India’s concerns, “maybe this is life”.

Clearly “life” in the maritime domain is shaped by the compulsions of power dynamics, with a correlation between global power status and maritime-naval prowess. Historically, both China and India have experienced humiliation in this arena, with Western imperial powers subjugating the two Asian giants on the back of superior maritime acumen.

Post Cold War, as Beijing grew in economic stature, it internalised its own maritime vulnerability and less-than-favourable strategic geography along its Pacific coastline. As a major trading nation, China was critically dependent on the safety and stability of its lines of communication through the Indo-Pacific continuum.

This stability was being underwritten by the principal hegemon of the 20th century: the United States and its allies. Clearly, this arrangement was irksome for Beijing, which began its own resistance as it enhanced its maritime heft.

Historically, major powers have sought unfettered access to two of the world’s three navigable oceans. It is why the UK, and later the US, tried to prevent Russia from reaching the warm waters of the Indian Ocean through Central Asia – a geopolitical competition known as the Great Game.

The larger community of Indo-Pacific nations caught up in the US-China and China-India rivalries are all stakeholders in what is currently at play: what are the agreed rules and norms at sea and who will enforce compliance if there is a transgression?

UNCLOS is interpreted subjectively and also mediated by power dynamics. Hence, there is an anomalous situation wherein the US is not a signatory to the law but is in reasonable compliance, whereas China is a signatory but has rejected rulings that it deems detrimental to its interests.

In the case of the Yan Wang 5, an expansive interpretation of the law would justify China’s position that the port visit to Hambantota was permissible, even while acknowledging India’s security concerns. In less brittle times, perhaps India could have dealt with this issue through quiet diplomacy, but that option has melted in an intrusive 24/7 news cycle with its rapacious appetite for “breaking news”.

India-China ties will improve with mutual trust, starting with border talks

Speaking in Bangkok on August 18, Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar observed that relations with China are going through an “extremely difficult phase” amid a military stand-off along their shared border in Ladakh in the Himalayas.

He added that it would be difficult to realise the goal of an “Asian century” if the two countries did not join hands.

Paradoxically, this tentative working together can begin in the maritime domain – as long as major powers have the political sagacity and each incident at sea does not turn into a “reach for your scabbard” dare.

As the Cold War demonstrated, committed professionals can evolve crisis-proof protocols for nurturing trust to avoid provocation and escalation – the tenet being that you can build trust and coexist, even without liking your adversary.

Commodore C. Uday Bhaskar is director of the Society for Policy Studies (SPS), an independent think tank based in New Delhi